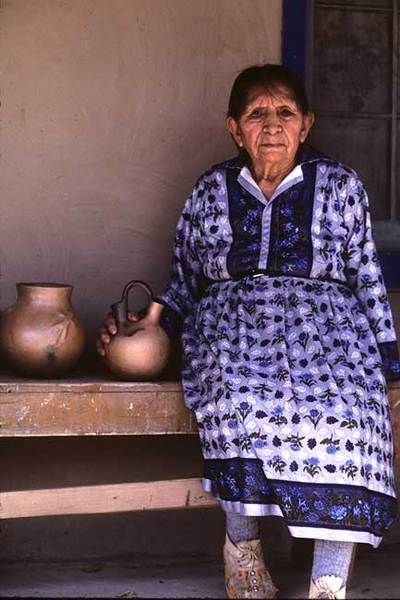

Virginia T. Romero

Nobody taught me how to make pottery. My mother made pots. I used to cook and do housework, but I saw her make them. I never thought I would touch the clay. Then one day my husband and my father went for clay. My father gave me a bag of clay and told me, “Daughter this will give you all you need—food, clothing and money.” And, you know, he was right. – Virginia T. Romero, 1989

Virginia T. Romero’s story provides a glimpse into the centuries-old traditions at Taos Pueblo (dating from 1350) and into the lives of its women. The daughter of Jose Pablo and Teodorita Martinez Trujillo, Virginia was born on ancestral land in September 1896. Her parents named her Pop Tő, which means “Flower House” in her native Tiwa language. By age 10, Virginia had learned to cook and take care of the house. Her training in the traditional ways of her tribe was interrupted by an educational system that took her away from her family before she entered her teens.

Virginia T. Romero’s story provides a glimpse into the centuries-old traditions at Taos Pueblo (dating from 1350) and into the lives of its women. The daughter of Jose Pablo and Teodorita Martinez Trujillo, Virginia was born on ancestral land in September 1896. Her parents named her Pop Tő, which means “Flower House” in her native Tiwa language. By age 10, Virginia had learned to cook and take care of the house. Her training in the traditional ways of her tribe was interrupted by an educational system that took her away from her family before she entered her teens.

In the early 1900s Virginia attended Santa Fe Indian School. Her father would take a day to drive his team of horses 19 miles to Pilar, New Mexico, the nearest train stop. The Denver & Rio Grande, completed in New Mexico in 1890, transported supplies, food and passengers, including Pueblo children who traveled between their reservations and boarding schools.

The U. S. government established these schools in the 1880s as part its country-wide assimilation program. The goal was to educate and indoctrinate Indian children into mainstream American culture by removing them from their homes and placing them in boarding schools. The isolation from their families caused homesickness and heartbreak. Away from home except for summers and Christmas holidays, the children missed out on the rich social and ritual life of their homelands. Thousands of young people suffered under the strict, harsh regimentation of an unfamiliar system. The Santa Fe Indian School, founded in 1890 as 1 of 25 off-reservation institutions, was charged with educating children from Southwest tribes. Geronima Cruz Montoya from San Juan Pueblo described her unhappy early experiences at the Santa Fe school:

We were not allowed to speak our native language. If we did we were punished, which made us feel ashamed of being Indians. It was a military type of school and we did a lot of marching—to meals, to assembly, to church, to salute the flag at sunrise. We did enough marching to last a lifetime.

When Virginia attended the Santa Fe institution, 60% of the 300 students came from the 18 northern and southern Pueblos, the rest consisted of Navajo, Hopi and other Southwest tribes. On the first day of school, boys and girls were separated and children assigned into companies by age group. The curriculum, taught in English, included arithmetic, geography, writing and history. Adjunct to academics, the children also received vocational or industrial training. Virginia and her classmates learned sewing, cooking, laundry and other housekeeping skills.

This training served Virginia in many ways. When she returned to Taos Pueblo, she married José de la Cruz Romero, widely known as Joe D. Romero, in 1920. The couple had ten children—Marina, Rose, Felipita, Jimmy, Paul, Catherine, Josephine, Tony, Teresita and Angelino—and Virginia used her sewing skills to make clothes for the entire family. Virginia was a gifted linguist. Besides her native Tiwa, she spoke Spanish and English. (Her family used to call her “Virginia Tech” because of her formal education.) As she was fluent in English and Spanish and could write in both languages, she served as interpreter for the tribal government.

Virginia devoted most of her time, however, to the welfare of her husband and children. Like most Taos Pueblo men of the time, Joe D. farmed to provide for his family. The main crops were corn, wheat, and oats. He and his sons worked the fields used by their family for centuries. They plowed the fields with horses, then dropped seeds into the soil. The men moved continuously, working the wheat in one plot and oats in another, and checking the corn growing in yet another field. Irrigating, hoeing, and weed control occupied them from sunrise to sunset. Virginia walked to the fields from their home on the south side of the pueblo to bring lunch to the men cultivating the fields. After their picnic of fresh, hand-made tortillas, pinto beans and green chilis, she returned home and with her daughters resumed the daily household tasks: laundry and other household chores, tending the vegetable garden, and baking bread in the hornos (outdoor beehive ovens made of adobe) until the time came to prepare the family’s evening meal.

The men also supplied meat. They caught fish from the rivers and numerous streams located on Taos Pueblo land. They hunted deer, elk and bear. Following the traditional way the men hunted rabbits, using bow and arrows and clubs. The women used the hides to make leggings, moccasins, boots and other buckskin apparel. Joe D. used horse hide, stretching it over hollowed out cottonwood stumps, to make drums. He also made quivers to hold the arrows he fashioned. Virginia made moccasins and the traditional white buckskin boots worn by Taos Pueblo women. She also beaded the quivers and moccasins and made beautiful shawls worn on special occasions by women. Her children remember the special buckskin gloves she made that covered her thumb and two forefingers. Virginia used them to pick piñons. Her special gloves allowed her to gather the nuts faster than any of her family members. She didn’t need gloves, however, to gather the wild mushrooms that grew in the forested canyons surrounding Taos Pueblo land.

The family lived off the land and from the work of their hands. They sold wheat and corn or traded their crops for goods like coffee, sugar or cloth. To earn money, the Romero family occasionally helped with construction projects. Clinton Anderson hired Joe D. and Virginia along with their sons to add rooms onto his house. Even the youngest helped. One of the children, probably 4 at the time, was too small to handle tools. He fondly remembers his elders throwing apples and oranges into the mud box where dirt, water and straw were mixed for making adobe bricks. As he searched in the box for the fruit (which sweetened his labor), the movements of his arms and legs mixed the mud and straw and so helped his family. When the rooms were enclosed, the women began plastering the interior: their traditional task in home building. Virginia designed and built the adobe fireplaces, adding the finishing decorative touch.

Such sculptural design abilities came from years of working with clay. Virginia began her career as a potter in 1919. As a child she had watched her mother shape clay into water jars, bean pots and dishes, the traditional cook ware of generations of Taos Pueblo women. After her father presented her a bag of clay, Virginia began making her own utilitarian ware. Virginia, her husband, sons and grandson made regular journeys to gather clay from a source about 11 miles from home (near the present Stakeout Restaurant). They traveled ten miles by horse-drawn wagon over rutted dirt roads, then up a canyon to gather bags of the tierra blanca (white earth) Virginia used to whitewash the interior of their home. The family got the micaceous clay she used for pottery at a site nearby. Her son Tony remembers that the family would get up at 3 a.m. to arrive at their destination by noon.

Back home, Virginia cleaned the raw clay, then ground it on a metate or grinding stone. She screened the ground clay and let it sit until it became “tender.” When the clay was ready, she divided it into a day’s worth of work: some 10 to 15 pots. After Virginia hand smoothed the signature mica clay into a variety of shapes and forms, she let them dry. When they were dry enough, she wood fired the vessels in her horno (outdoor oven) until they glowed red-hot. In her 80 years as a potter, she never lost a pot in the firing. She attributed that success to the fine grind of her clay.

Only two Pueblos—Taos and Picuris—use micaceous clay to make pots. From the 1400s on potters (always women in those days) from both tribes decorated their pottery. Following the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, however, they created plain vessels in the style of their Jicarilla Apache neighbors. The only decoration comes from the “fire clouds” (or smoke stains resulting from the firing process) that enhance the characteristic burnished bronze colored vessels with their shimmering flecks of mica.

The first pieces Virginia created were probably cooking pots, dishes and other household ware for family use. Once she mastered her craft, she began selling bean pots and lidded water jars to locals and to tourists. (When micaceous clay is fired, it becomes waterproof.) Before long her work evolved into more decorative pieces. Virginia started making wedding vases, cylindrical vessels with added sculptural lines, and rimmed bowls. Her innovative work drew on the pots of her ancestors and on her home environment. Virginia was the first to make miniature hornos, honoring the outdoor oven used both to bake bread and to fire her pots.

The first pieces Virginia created were probably cooking pots, dishes and other household ware for family use. Once she mastered her craft, she began selling bean pots and lidded water jars to locals and to tourists. (When micaceous clay is fired, it becomes waterproof.) Before long her work evolved into more decorative pieces. Virginia started making wedding vases, cylindrical vessels with added sculptural lines, and rimmed bowls. Her innovative work drew on the pots of her ancestors and on her home environment. Virginia was the first to make miniature hornos, honoring the outdoor oven used both to bake bread and to fire her pots.

In the 1930s, collectors from neighboring states began purchasing Virginia’s pottery. Clark Field, an Oklahoma businessman, acquired two of her ceramic pieces in 1939. They became part of an incredible collection of Pueblo pottery dating from the early 1900s to about the 1950s that Clark later donated to Tulsa’s Philbrook Museum of Art. Oklahoman Frank Phillips of Phillips Petroleum Company bought eight of Virginia’s ceramics as part of his museum-quality collection of Native American art.

Virginia traveled throughout New Mexico and Oklahoma to show and sell her work. She won prizes and acclaim at the Santa Fe Indian Market and at the annual intertribal ceremonial exhibition in Gallup. Indian people also recognized Virginia’s work. In 1960 The Inter-Tribal Indian Ceremonial Association present her with a certificate of merit for “producing and exhibiting Indian arts and handicrafts of prize-winning quality.” As her fame grew, museums and private collectors in the United States, Japan, Germany and other countries places began collecting Virginia’s pottery. Some museums that house Virginia’s work include The Los Angeles County Museum, the Southwest Museum of the American Indian (now part of the Autry National Center in Los Angeles), the School of American Research and the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, and the Millicent Rogers Museum in Taos.

As her father had predicted, the clay gave Virginia all she needed. Money earned from the sale of her pots (and the sale of Joe D.’s drums) supported the family. For all the acclaim from the outside world, Virginia continued the traditional ritual life at Taos Pueblo. Like her ancestors, she instructed her children in the lifeways of her tribe. She also taught pottery techniques to young children at the Oo-ooh-nah Children’s Art Center. Virginia supported her husband when tribal officials elected him Governor of Taos Pueblo in 1976. She participated in women’s dances held in the spring and at Christmas time. The backbone of Taos Pueblo, Virginia and other women homemakers cooked for and participated in feast days like the annual San Geronimo Day on September 30th and the Christmas Eve and other winter celebrations.

In September 1994 the Millicent Rogers Museum honored Virginia and her long career as a potter. At age 99 she was the first Taos Pueblo person to receive such recognition. Besides her children, grandchildren, and Taos Pueblo tribal members, many admirers from the Taos community attended the event. The Red Pine drummers opened the ceremony with an honor sung in Tiwa. The museum presented Virginia with a plaque in recognition of her dedication and commitment to the arts. A Taos Pueblo official spoke (in Tiwa and in English), congratulating Virginia and acknowledging her work as part of the art that made Taos famous. He hoped that young people would aspire to reach her height of achievement. Tribal elder Tony Reyna, who had served his people as Governor and in other tribal government positions, thanked Virginia for her encouragement and support of youngsters at the Oo-ooh-nah Center. After the speeches, Virginia’s daughters and women from the Pueblo supported Virginia in the Round Dance. They circled the room, sidestepping in graceful, swaying motions in rhythm to the Red Pine drum and song. Women from the museum staff joined in this social dance, a fitting ending to the evening’s festivities.

Virginia continued to make pots up to her 100th birthday in 1995. The death of her beloved husband Joe D. in 1993, and a few years later a broken hip, slowed her down. Virginia’s devoted children took turns caring for her, and one of them was with her at all times until her death 1998. Her pottery legacy continues through generations of her family and young people she encouraged and inspired. Both her daughter Catherine and her daughter-in-law Viola became potters; Virginia’s son Paul, a skilled woodworker, designed the doors for the San Geronimo church at Taos Pueblo; many of Virginia’s children and their descendants are artists.

In 2005 the New Mexico Women’s Forum and the State of New Mexico honored Virginia T. Romero with an Official Scenic Historic Marker. It is located on State Highway 150 in sight of her grandson’s family home on Taos Pueblo land.

Virginia Romero’s pottery is on permanent display at the Millicent Rogers Museum. (While visiting, be sure to look at the fireplaces she created—the Millicent Rogers Museum collection is housed in the former Clinton Anderson home.)

For further information, please visit The Millicent Rogers Museum site, www.millicentrogers.org

Photo © 2012 Stephen Trimble from Talking With the Clay: The Art of Pueblo Pottery in the 21st Century www.stephentrimble.net

By Elizabeth Cunningham, 2012

Blog host, “Mabel Dodge Luhan and the Remarkable Women of Taos”