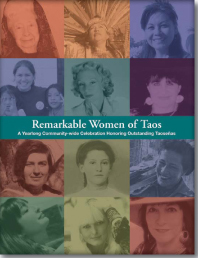

Josefa Carson and Ignacia Bent

Hispanic women of New Mexico found their sense of identity in belonging to la familia, an extended family in which their role as housekeeper, bearer of children, and caregiver was highly valued in the community. Nevertheless, authority was tightly concentrated in the hands of the male head-of-household, so that his wife and other female members were accustomed to having his paternalistic rule, be it benevolent or harsh, guide them in everyday matters both large and small.

Marc Simmons, Kit Carson & His Three Wives: A Family History (2003)

Two sisters, descended from one of New Mexico’s oldest and most respected families, played an important role in the history of Taos during the tumultuous 1800s. Maria Ignacia Jaramillo and her younger sister, Maria Josefa, were each married to famous men. For that reason fragments of their stories survive in print, and illuminate the lives of 19th-century Hispanic women. Life was very different back then – particularly for women. 2012 marks the Centennial of New Mexico statehood and more history of Northern New Mexico, Taos, and women of the west may be found at www.newmexicohistory.org.

Two sisters, descended from one of New Mexico’s oldest and most respected families, played an important role in the history of Taos during the tumultuous 1800s. Maria Ignacia Jaramillo and her younger sister, Maria Josefa, were each married to famous men. For that reason fragments of their stories survive in print, and illuminate the lives of 19th-century Hispanic women. Life was very different back then – particularly for women. 2012 marks the Centennial of New Mexico statehood and more history of Northern New Mexico, Taos, and women of the west may be found at www.newmexicohistory.org.

By the time Charles Bent began a family with Maria Ignacia Jaramillo in 1835, he was a renowned trader. He started working for the Missouri Fur Company in 1822. He soon became a partner owner and helped with reorganization efforts. Within seven years the company flourished due to his business acumen and knowledge of Indian country west of St. Louis. It could not compete, however, with the American Fur Company. Consequently Charles set his sights on the burgeoning Santa Fe trade. In 1829, at age 30, Charles and his younger brother William escorted a caravan of 93 wagonloads of goods from Missouri to New Mexico. After this highly lucrative expedition, Charles went into business with Frenchman and fellow trapper Ceran St. Vrain. Their firm Bent, St. Vrain and Company became one of the West’s leading mercantile enterprises. Annual profits from the fur trade alone averaged $40,000. The partners opened stores in Santa Fe and in Taos where St. Vrain had resided since 1826.

In 1833 Charles, his brother William and St. Vrain established Bent’s Fort. Built in 1833-34, the immense nearly 170 feet square adobe structure, constructed by Hispanic masons from Taos, protected their trade goods and supplies. Located strategically at the confluence of the Arkansas and Purgatory rivers, this settlement in southeast Colorado served as a major trade center between trappers and Plains tribes. According to Bent’s daughter Teresina, the Bents were known for fair treatment which won them the respect of “Indians of all tribes, the French and American trappers and traders” as well as emigrants, and officers and service men of the U. S. Army.

At the time the centuries-old Trade Fair also made Taos a favored base of operation. Starting in the late 1700s French Canadian and American trappers had come to the area to procure hides and exchange goods with regional Indian tribes and long-time resident Hispanos. Decades later, trade drew the Bent brothers and St. Vrain, and other renowned mountain men like Hugh Glass, Ewing Young, Baptiste LaLande, and Kit Carson to northern New Mexico.

At the time the centuries-old Trade Fair also made Taos a favored base of operation. Starting in the late 1700s French Canadian and American trappers had come to the area to procure hides and exchange goods with regional Indian tribes and long-time resident Hispanos. Decades later, trade drew the Bent brothers and St. Vrain, and other renowned mountain men like Hugh Glass, Ewing Young, Baptiste LaLande, and Kit Carson to northern New Mexico.

Highlighting some of the dramatic differences in our society today and 150 years ago, besides commerce, the beauty of Taos women provided an attraction as described in accounts of the period. One written by young Lewis Garrard, who arrived with a contingent of mountain men in spring 1847, provides a rare printed depiction of particular Taos women, including Ignacia Bent. Garrard portrayed her as

Quite handsome; a few years since, she must have been a beautiful woman—good figure for her age; luxuriant raven hair, unexceptional teeth, and brilliant, dark eyes, the effect of which was heightened by a clear, brunette complexion.

Ignacia was then about 33, which must have seemed old to this young man of 17. Garrard was smitten, however, with her younger sister who was nearly his age. To him Josefa had a style of beauty “of the haughty, heart-breaking kind” that would “lead a man to risk his life for one smile.”

Frontiersman Kit Carson evidently shared Garrard’s opinion. He had met Josefa while visiting Charles Bent at his home in Taos when she was “just a slip of a girl.” Lovesick, he bided his time. When she reached the marriageable age of 14 he began to court her. He evidently won her heart but not the approval of her father, the prominent and formidable Francisco Estaban Jaramillo. In 1842, in order to prove his serious intent, Carson converted to Catholicism. Perhaps Carson’s land holdings, his prowess as a trapper and success as a guide for explorer John C. Fremont’s first expedition to Wyoming’s Wind River country improved his prospects. Or the fact that he wanted to officially marry Josefa (although Charles Bent had several children with Ignacia, he hadn’t wed her) finally won over the Jaramillo family. Nearly a year later, on February 6, 1843, Kit and Josefa were married by the parish priest, Padre Martinez, at Our Lady of Guadalupe church. Their padrinos, or sponsors, were Charles Bent’s younger brother George and his common-law wife María de la Cruz Padilla. Carson bought a house for his new bride, only to spend six months on and off over the next six years there with her in Taos. His work as a guide, soldier, government agent and courier took him away from Josefa. Except for a brief period between 1854 and 1861 when he worked as an Indian agent in Taos, Josefa experienced her husband’s prolonged absence.

Charles Bent’s commercial ventures—tending to business at the fort, looking after the Santa Fe store—caused him to be away from his family and home in Taos. When he met Ignacia Jaramillo, she was a handsome young widow with a daughter named Rumalda. Bent took her as his common law wife and adopted Rumalda. The three lived in a small adobe just north of the village plaza and about 3 miles from Taos Pueblo. In their home, Ignacia gave birth to the first of the couple’s five children (only three survived infancy). She managed the household and sheltered Rumalda who had married Tom Boggs (The Bents considered the mountain man a nephew and Boggs was Carson’ closest friend and associate.). Carson, six years older than Ignacia, fondly referred to her as the “old lady.” Along with Bent and Boggs, he counted on her to take care of their families while they conducted business outside Taos.

Carson was serving in California with Fremont in May 1846 at the outbreak of the Mexican War, a U.S. conflict waged between 1846 and 1848. His work involved carrying dispatches between command posts in enemy territory. This dangerous duty kept Carson apprised of developments throughout the Southwest. He learned of the U. S. government’s intention to annex land east of the Rio Grande. Colonel Stephan Watts Kearny received orders to lay claim to California and to annex all of New Mexico. When the annexation proclamation reached Taos, Carson feared for Josefa’s safety—for good reason.

Kearny informed Manuel Armijo, then Governor of territorial New Mexico under Mexican rule, of the U.S. government’s intent to annex New Mexico. Sensing major trouble, Governor Armijo deserted. On August 18th 1846 Kearny, now Brigadier General, raised the American flag and fired a 13 gun salute at the Palace of the Governors as he informed the populace of New Mexico’s capital of the pending annexation. Upon hearing the proclamation, prominent New Mexicans were outraged at U.S. aggression and ashamed of Armijo’s desertion. They began making plans to defend their country against American occupation. In September Kearny appointed Colonel Sterling Price military governor and Charles Bent civil governor of New Mexico. Bent appointed his trader and merchant friends—and Donacio Vigil from Armijo’s administration—to governmental positions. Although his new administration swore allegiance to the United States, the rest of the territory dissented. A rebel conspiracy formed to expel the military and civil government. Despite warnings of a revolt, Bent left the tense atmosphere of Santa Fe.

On January 14, 1847 he set off through the wintry cold for Taos intent on dispelling discontent and seeing his wife and children. Three days later yelling awakened the Bent family in the early morning hours. When Charles opened his door in hopes of calming the crowd gathered there, he was shot in the leg. Ignacia pulled him inside, and bolted the door shut. She urged her husband to flee, but he refused. While the enraged throng chopped through thick adobe, Rumalda Boggs and Josefa used a spoon and a poker to dig through the walls of the adjoining house. When the opening was large enough, the women pushed their terrified children through the hole, then followed. Ignacia urged her husband to flee with them just as the first rebel burst into the room. Bent, shot through with arrows, then scalped, urged his wife to flee with the family. She had been wounded and, had her Pueblo servant not stepped in front of her, would have been shot dead. Ignacia and her husband got as far as the adjoining room before a man reached them and shot Bent in the face with a pistol. While she knelt by her slain husband, the story goes, Josefa and Rumalda begged the bloodthirsty mob for mercy. Luckily for them town resident Buenaventura Lobato entered the Bent house and, too late to save Charles Bent, intervened and spared the women’s lives. The attackers departed leaving the Bent family in a state of shock. Left wearing only their night clothes, they stayed in the house through the following night. Courageous friends supplied them with food and blankets, then Ignacia and her children escaped to the home of Juan Catalina Valdez. Another family sheltered Josefa and Rumalda, and to ensure their safety disguised them as household Indian servants.

The family tragedy did not end with Charles Bent’s assassination. In defense of their country, the defiant insurrectionists hunted down and killed anyone or destroyed anything connected with the murdered man. They found Ignacia and Josefa’s brother Pablo Jaramillo and his friend Narciso Beaubien and lanced them to death. The rebels destroyed the personal property of Rumalda’s grandfather and pillaged the Carson home, robbing it of everything. Retribution for these and other crimes came on February 3, 1847. U.S. troops headed by Ceran St. Vrain marched on Taos plaza. When the rebels fled for the sanctuary of Taos Pueblo’s church, the Army shelled the adobe structure in an all-out attack. By the end of the day, the U.S. troops had quelled the rebellion and 150 defenders had died in the fight.

In the series of trials that followed, Ignacia, Rumalda and Josefa were called on as eyewitnesses. Lewis Garrard, who would publish Wah-To-Yah and the Taos Trail about this troublous time, attended the trials and stated, “The dress and manner of the three ladies bespoke a greater deal of refinement than usual.” Giving testimony, and so reliving the horror of Bent’s murder, must have been excruciatingly painful for the three women. A glimpse of how it affected them was indicated in an interview Ignacia granted to Lt. John G. Bourke in 1881. Recounting her husband’s slaying, her voice quavered and her eyes brimmed with tears.

Kit Carson learned of the Taos revolt three months later. When he rode into Taos on April 9, 1847 after guiding Fremont’s third expedition, Josefa told him what had transpired. The loss of Charles Bent, Pablo Jaramillo and other friends and family members embittered him. With their deaths came new responsibilities, including taking charge of the Bent children. Carson and Josefa became Teresina’s guardian and Ceran St. Vrain had custody of Estafina. Teresina later recalled that whenever the children left home, they were accompanied by Carson, St. Vrain or an escort provided by the two men. The Taos rebellion had left deep, lasting scars.

No matter how long he was away, Carson’s family remained important to him. A junior officer recalled him lying on a blanket with his pockets stuffed with candy. His children jumped on top of him, raided his pockets, and ate the candy. Clearly such small episodes brought him great pleasure. And all his happiness depended on Josefa. Teresina Bent, who lived with the Carsons, once described Josefa as follows: “Rather dark [complexion], very dark hair, large bright eyes, very well built, graceful in every way, quite handsome, very good wife and the best of mothers.” Teresita also related Josefa’s hospitality:

The Carson door was always open to neighbors: Indian, Spanish and Anglo, and to it also came practically every representative of the Catholic clergy, including Bishop Lamy a family friend, [and]every renowned writer and traveler, and army officer who came to New Mexico.

When the intrepid explorer John C. Fremont, weakened from near starvation, staggered into Taos in January 1849, Kit took his friend home to Josefa. Under her care, Fremont regained his strength and his mental equilibrium following his disastrous Fourth Expedition. Commissioned to search for a railroad route from the central Rockies to California in 1848, he had lost ten men and nearly perished himself in the heavy snows of Colorado’s La Garita Mountains (northwest of present Del Norte). Later in a letter to Kit, Jessie Benton expressed her gratitude for the kind care her husband had received from Josefa. Fremont had his own fond memories of Josefa, whom he held in high esteem as a New Mexican lady of great worth.

One of Josefa’s most loving actions showed the depth of her love for her husband. In early 1868 Carson began suffering acute pain in his chest and neck. Around the second of April, Kit stopped in Pueblo en route to join his family in Boggsville, Colorado. In distress, he sent for the town physician who found a bulge in the carotid artery—a weakened wall that could burst any moment. Somehow Carson let Josefa know of his pending arrival. Although near term with her 8th pregnancy, she persuaded Tom Boggs to drive her in the family carriage to intercept her husband. She reached him near La Junta (about 20 miles west of Boggsville) and the couple returned home to their children. Reunited with his family, Kit’s health improved enough for him to consider building a house on his land. Everything seemed to be improving. Then after Josefa gave birth to her baby on April 13th, instead of rallying she grew increasingly weak. Fourteen days later she called out to Kit in Spanish. He rushed to her side and held her. She spoke her last words to him then died in his arms.

Carson pined for his wife and his health declined. He wrote Teresina’s husband Aloys Scheurich with instructions to move Josefa’s body and his, if he should die, to be buried in the family graveyard in Taos (today they are both in the Kit Carson Cemetery in the center of Taos in Kit Carson Park. Many other famous Taos individuals are also buried there.). Carson added:

Please tell the old lady [Ignacia] that there is nobody in the world who can take care of my children but her, and she must know that it would be the greatest of favors to me, if she would come and stay until I am healthier.

Ignacia and Teresina Bent Scheurich hastened to Boggsville. When they arrived, Tom Boggs told them that Kit was so weak that he couldn’t see them. Nor could he see his beloved children. Knowing that they would soon be orphans, it was too painful for him to bear. Carson never regained his health. He died on May 23, 1868. After his death, Ignacia became the Carson children’s guardian. She cared for them until her death in 1883.

The lives of Ignacia and Josefa serve as exemplars for Hispanas of the 19th century. Their stories are representative of a multitude of courageous, resourceful women in Taos and throughout the Southwest. When their men found work elsewhere, these women nurtured their families, tended huge gardens, took care of the livestock and cultivated crops, prepared and preserved food, and even fought off marauders. This tradition continues today, a legacy left by Ignacia, Josefa and countless Hispanic women whose stories will never be known.

To see the Taos homes where Ignacia and Josefa lived and learn more about them, please visit the Governor Bent House and Museum (117 Bent Street) and the Kit Carson Home & Museum (113 Kit Carson Road).

And for in-depth history and a fascinating read, get a copy of Kit Carson and His Wives: A Family History by the eminent New Mexico scholar and historian Marc Simmons.

By Elizabeth Cunningham, 2011

Blog host, “Mabel Dodge Luhan and the Remarkable Women of Taos”

Pictured above, Maria Ignacia Jaramillo Bent (ca. 1814-1883)

Pictured below, Maria Josefa Jaramillo Carson (1828-1868)