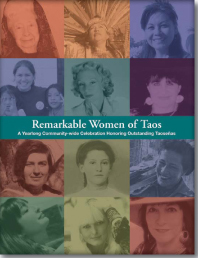

Two Classics: Cecil Dawkins and Cynthia Homire

Two Classics: Cecil Dawkins, Writer and Cynthia Homire, Potter and Poet

The telling of Cecil Dawkins’ story also encompasses the account of another remarkable woman of New Mexico. Born in Birmingham, Alabama in 1927, Cecil pursued her passion for writing from childhood. After graduating with a B.A. in English from the University of Alabama in 1949, she was a member of Wallace Stegner’s writing seminar at Stanford University where she was awarded the 1952-1953 Creative Writing Fellowship (now the Wallace Stegner Fellowship) and also earned an M.A. in English Literature.

The telling of Cecil Dawkins’ story also encompasses the account of another remarkable woman of New Mexico. Born in Birmingham, Alabama in 1927, Cecil pursued her passion for writing from childhood. After graduating with a B.A. in English from the University of Alabama in 1949, she was a member of Wallace Stegner’s writing seminar at Stanford University where she was awarded the 1952-1953 Creative Writing Fellowship (now the Wallace Stegner Fellowship) and also earned an M.A. in English Literature.

While Cecil was teaching at Stephens College in Columbia, Missouri, a young professor from the University of Missouri, who came to dinner with his wife, tossed a paperback of short stories on the table saying “You’ve got to read this.” It was Flannery O’Connor’s first story collection. Cecil read the stories late into the night and, greatly impressed, immediately wrote a letter of admiration to the author. Thus began a correspondence between the two young writers that lasted until O’Connor’s death in 1964. Cecil visited O’Connor on her family farm, Andalusia, in Milledgeville, Georgia. O’Connor admired Cecil’s work and became her reader. Cecil’s short stories, first published in such literary quarterlies as the Paris Review, the Sewanee Review and others, were brought out in 1963 by Atheneum in New York City and by Andre Deutsch in London. The Saturday Review magazine deemed the collection, written in the spirit of Eudora Welty and Katherine Anne Porter, as “superior stories, surprising in their depth of understanding and remarkable in their craftsmanship.” One of the stories appeared in Best Short Stories of 1963 and won an award in Southwest Review as well as the John H. McGinnis Award for the Best Story in Two Years.

Flannery suggested that Cecil apply for a residency at the Yaddo artists' community in Saratoga Springs, New York. The usual residency period was granted for two months, but because the Board liked her work Cecil was in residence for six. In 1966 she received a Guggenheim Fellowship. Cecil’s play, The Displaced Person, based on stories by O’Connor (with O’Connor’s permission and input) was then in preparation and production at the American Place Theater in New York City. The play ran during the theater’s 1966-1967 season. Since the project engaged Cecil throughout her Guggenheim year, the foundation awarded her an extension to work on her from her novel-in-progress in 1967. When Harper and Row published her first novel The Live Goat, the book won a Harper-Saxton Fellowship in 1976. Cecil’second novel, Charleyhorse, was published by Viking in 1985. Viking also brought it out in paperback as part of its Contemporary American Fiction series. Author Diane Johnson’s blurb stated “It’s wonderful to have a new book from Cecil Dawkins.”

Cecil came to the Wurlitzer Foundation in Taos in 1969, fell in love with Taos and decided to stay. She walked into the nearest real estate office and met Frances Martin the broker. Frances showed her eleven acres in Des Montes (northeast of Taos) with views of Taos Valley, Taos Mountain, the desert and the Rio Grande Gorge. She purchased the land and lived in a camping tent for the summer in the orchard while rebuilding an ruin that became part of her adobe house. Cecil did the work herself with the help of visiting friends and friends the Wurlitzer.. The land bordered the property of the Romero sisters, Mercedes and Adelaida. Cecil and Adelaida became staunch friends, eventually irrigating their joined pastures together and caring for their animals: Adelaida’s cows and Cecil’s horse and little mule. As they each had a pickup and chain saws, they ventured out in the forest together and cut their own winter wood.

Cecil took inspiration from her friend Frances Martin (nee Francis Minerva Nunnery, her maiden name used in the title of her autobiography as later translated and edited by Cecil). Cecil learned that this tough, self-made woman had worked on a Virginia tobacco farm as a girl, then at the Heinz Plant in Pittsburgh in her teenage years. Shipped off to Colorado at age 21 to marry a man she didn’t know, Frances escaped with her daughter and their lives to New Mexico. She settled in Albuquerque where among other occupations she worked as a chauffeur, bus driver, boarding house keeper, night club singer and used car dealer. Before her arrival in Taos, Frances had owned and run the Centerfire and Spur ranches in Catron County (she traded cars for cows to get her start) where she had also worked as a deputy sheriff. Frances had always fixed up her own places. In the 1950s she was the first to recognize the value of sagebrush land. She eventually developed seven subdivisions on sage land around Taos. Frances lived in Taos until arthritis got the best of her. She moved to Truth or Consequences in 1978, and later to Silver City. Cecil, who sold her Taos place in the mid-1980s and moved to Santa Fe, kept in touch with Frances until her death in 1997.

In 2002 Cecil transcribed and edited Frances’ taped-recorded recollections into a riveting memoir. Adding a preface and afterword, Cecil sent the completed manuscript to the University of New Mexico Press. A Woman of the Century, Frances Minerva Nunnery (1898-1997): Her Story in Her Own Memorable Voice as Told to Cecil Dawkins appeared in 2002. The book won acclaim from the Santa Fe New Mexican: "[Nunnery's] journey through the 20th century provides a fascinating picture of New Mexico in earlier times, and of a remarkable character who gives new meaning to the phrase 'a woman's work'.” In her afterword, Cecil wrote “We learn who Frances was from what she did. Like the pioneer women, she was nothing if not a survivor, and like her mother she could do anything. Her success was based on her willingness to undertake any job and, if it didn’t work out to suit her, to try something else.”

While living in Santa Fe, prior to tackling the memoir on Frances, Cecil began writing in a new genre. It started on a dare. Cecil had been teasing a friend for reading mystery stories, who in turn challenged her to write her own. With no serious writing in mind to work on, Cecil wrote four mysteries—The Santa Fe Rembrandt (1993), Clay Dancers (1994), Rare Earth (1995) and Turtle Truths (1997), all set in northern New Mexico, a place she knows and loves. Throughout her writing career, Cecil held several academic positions as writer-in-residence and guest lecturer. These included two years at Sarah Lawrence College (1979-1981), and the Fuller E. Calloway endowed Chair in Creative Writing (1996-1997) at Georgia College in Milledgeville, Flannery O’Connor’s alma mater. Now resettled in Taos, Cecil Dawkins’ fondly recalls her days of hiking and backpacking in the surrounding Sangre de Cristos.

.jpg) The maverick spirit of Black Mountain College appealed to Cynthia Homire’s adventurous nature. The place had aroused her interest while at Swarthmore High in Pennsylvania. Cynthia’s first direct connection happened while attending Windsor Mountain School in Lenox, Massachusetts. Three of her instructors, fresh from studies at Black Mountain, reinforced the progressive education she received at Windsor. She took a class with Jane Slater Marquis who had studied with the Bauhaus designer, artist, and art theoretician Josef Albers. The possibilities of montage, collage and painting excited Cynthia. Driven by the desire to learn more, she wanted to study with Albers.

The maverick spirit of Black Mountain College appealed to Cynthia Homire’s adventurous nature. The place had aroused her interest while at Swarthmore High in Pennsylvania. Cynthia’s first direct connection happened while attending Windsor Mountain School in Lenox, Massachusetts. Three of her instructors, fresh from studies at Black Mountain, reinforced the progressive education she received at Windsor. She took a class with Jane Slater Marquis who had studied with the Bauhaus designer, artist, and art theoretician Josef Albers. The possibilities of montage, collage and painting excited Cynthia. Driven by the desire to learn more, she wanted to study with Albers.

Although her mother had championed Bryn Mawr in Pennsylvania, Cynthia held out for Black Mountain College in North Carolina. She knew that the experimental, interdisciplinary institution, co-run by faculty and students, had served as an incubator for the American avant garde. From 1933 to 1957 the college attracted faculty and lecturers like Josef and Anni Albers, Buckminster Fuller, Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg, Robert Creeley, Charles Olson, and M.C. Richards. Some of the students later became America’s leading designers, poets and artists, among them painters Willem de Kooning and Cy Twombly. Cynthia applied to study at Black Mountain in 1949 and enrolled for the following year. To her disappointment, Josef Albers had just departed to head the Design Department at Yale University and was no longer teaching. Undeterred, Cynthia stayed on for four years. Her most influential teachers were poets Charles Olson and Robert Creeley, and the multi-faceted poet, potter, painter and translator M. C. Richards.

Students inundated Charles Olson’s class just to hear him talk. They found him fascinating. Throughout his life he encouraged many young writers. According to Cynthia, Olson tired of students coming only to listen to him. He issued an ultimatum: “Either write or don’t come to class.” She chose to write a story. After Olson read it, he said “If you write a hundred of these, I’ll get you published.”

What Cynthia had to say about her experience at Black Mountain College gives a taste of both her sense of humor and what life was like there for her as a young woman:

Yes, I have rubbed shoulders with the pantheon, a few bellies, too. Washed the floor Merce Cunningham danced on, then went leaping through his class. Jitterbugged with Rauschenberg, pointed out morels to John Cage, was instructed by Olson in long night classes to write from my roots, dirt and all, but take time out to dig up a few Mayans in Mexico. Shared steak with William Carlos Williams (he said "I know you"). Cooked a Chinese meal for Eliot Porter and David Brower (before David took to chewing each bite thirty times before swallowing). Breakfast with Brautigan. All these things happen if you are there for them and maybe you make pots for 30 years and then maybe you write poetry.

Instruction from M. C. Richards, who taught writing and produced plays and took pottery classes from Robert Turner, was casual and hands-on. When Cynthia wandered into the pottery studio, she found M. C. at work. When asked how to make a pot, M. C. told Cynthia to center the clay on the wheel. After success in drawing up the clay to make a cylinder, she asked M. C. what to do next. “You’re so smart, make a teapot,” she replied.

Then living in New York City, Cynthia worked for the Congress of Racial Equality. She kept in touch with M. C. when she asked Cynthia to housesit. In trade for tending M. C.’s garden and looking after her cats Cynthia could work in the studio. She also “filched” a carbon copy, rescued from the trash, of the first copy of M. C.’s book, Centering in Pottery, Poetry and the Person (1964). The book became an underground classic. Master potter Daniel Rhodes called it “a poem, a sutra, a tract, a confession, a revelation, a guide to art and life.” Its poems and essays, which argue for creativity and the richness of daily life, still resonate with Cynthia.

When she searched for a creative outlet, her mentor told her about the Clay Art Center in Connecticut. It was a place where “you could just go and be a potter.” For a monthly fee potters could house their wheels and equipment and have a space to work. Additional fees were charged for glazes and for firing their pieces. This suited Cynthia. In such an environment she was free to experiment with various forms of utilitarian ware, beginning with teapots, cups, platters and goblets.

While enrolled at Black Mountain Cynthia met fellow student Jorge Fick. They both took theater and Spanish classes. Cynthia recalls them practicing “silly Spanish” like Donde esta mi sombrero? A painter, Jorge was the last student to graduate from the school. With the Abstract Expressionist Franz Klein as his “outside examiner,” Jorge got his Bachelor of Fine Arts in 1955. After a painting stint in New York City where his mixed-media compositions were exhibited at Stable Gallery with early works by Willem de Kooning and Robert Rauschenberg, Jorge reconnected with Cynthia in 1964. Then living in New Mexico, he said “We need a potter in Santa Fe.” Within a week the two married. Once settled in nearby La Cienega, the couple opened the Fickery on Canyon Road in Santa Fe. From 1972 to 1983 they sold utilitarian stoneware made by Cynthia and glazed by Jorge until the time he “retired” so he could paint. Their life was full. On Saturdays they hosted a morning life drawing class. Afterward they lunched at the same Mexican restaurant. Cynthia and Jorge loved Weimeraner dogs and kept several of them over the years. At one time they had a pig named Pinkus. He was supposed to be a pot-belly pig but grew to be quite large and pushy. Accustomed to growing her own produce, Cynthia gardened every season and canned for the winter.

Everything changed when Cynthia’s eyesight began to fail. It caused her to move to Portland, Oregon in 1990. Her sister lived there and the city with its outstanding Service Commission for the Blind program helped Cynthia learn to live with sight impairment. Longing for New Mexico she moved to Taos in 1998. Among the people she already knew there were several fellow Black Mountain students, including Rena Rosequist and Barbara and Cliff Harmon. Cynthia became involved with the arts community and poetry replaced pottery. In 2008 she self-published and illustrated Insights & Outbursts, a collection of poems written between 2005 and 2007. Just recently she produced a whimsical series of collages using banana peels. One, a figure sitting with legs crossed, she titled Buddhana. As with Robert Rauschenberg, for Cynthia the world is her palette: her life is art, her art is life. Asked what’s important to her, she replies “Imagination,” then adds “And seeing where it takes you.”

By Elizabeth Cunningham

Cecil Dawkins. Photo ©2012 by Megan Bowers Avina

Cynthia Homire. Photo ©2012 by Kathleen Brennan