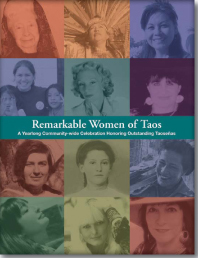

Mabel Dodge Luhan

Art Patron and Writer (1879 – 1962)

She was a woman of profound contradictions. She was generous. She was petty. Domineering and endearing. She was Mabel Gansen Evans Dodge Sterne Luhan – salon hostess, art patroness, writer and self-appointed savior of humanity.

She was a woman of profound contradictions. She was generous. She was petty. Domineering and endearing. She was Mabel Gansen Evans Dodge Sterne Luhan – salon hostess, art patroness, writer and self-appointed savior of humanity.

Mabel Ganson was born into wealth in Buffalo, New York. Her unhappy upper class parents, who lived off an inheritance provided lavishly for their only daughter, but wholly neglected her emotionally and spiritually. Mabel grew up in a family and society that placed value on appearances and the lack of purposeful activity. With such an emotional void in her life, it was no wonder that she created her own worlds.

Eager to flee this repressive home atmosphere, Mabel married Karl Evans in 1900. After giving birth to her only child, she found marriage and motherhood just as stultifying as her childhood years. After Karl died in a hunting accident, Mabel departed for Europe with her son John. In Paris she met the wealthy Boston architect Edwin Dodge. He pressed his suit until she agreed to marry him in 1904. For Mabel this was no love match. She wed Edwin to have a father for John and for the security and luxury he offered her. The Dodges settled in Florence, Italy. They lived at Villa Curonia, a magnificent estate originally built for the Medicis. Here Mabel began to recreate herself. She did so in the context of the Renaissance, which expressed her aesthetic impulses. She invited Italian nobility, artists and writers of the day to grace her salon and share her table. Her guests included Bernard Berenson, the famed American art historian who specialized in the Renaissance, and another salon hostess, Gertrude Stein, and her brother Leo.

By 1912 Mabel found Europe and Florence aesthetically and emotionally bankrupt. Further, as her son John had now reached adolescence, she saw no further reason to stay with Edwin and separated from him after the Dodge’s return to New York. Freed from the confines of marriage, Mabel heeded the advice of her new friend, the muckraking journalist Lincoln Steffens. Steffens believed that Mabel had a certain faculty, a “centralizing, magnetic, social faculty” as he related over tea at her home one afternoon:

You attract, stimulate, and suit people, and men like to sit with you and talk to themselves! You make them think more fluently, and they feel enhanced. If you had lived in Greece long ago, you would have been called a hetaira. Now why don't you see what you can do with this gift of yours? Why not organize all this accidental, unplanned activity around you, this coming and going of visitors, and see these people at certain hours. Have Evenings!"

Mabel soon presided over one of the most famous salons in American history at 23 Fifth Avenue.

From 1913 to 1916 she hosted “Wednesday Evenings” at her New York home, a gathering spot for pre-World War I "movers and shakers" who supported avant-garde ideas in the arts, politics and society. Revolutionary at the time, salon topics ranged from psycholanalyst A. A. Brill discoursing on the ideas of Freud, journalist Hutchins Hapgood debating the virtues of free love, or Emma Goldman presenting an anarchist's view of working-class struggles.

Through Gertrude and Leo Stein in Paris, Mabel was familiar with paintings by Picasso, Matisse and other modern painters. She found an equivalent at Alfred Stieglitz’s “291” gallery, considered the center of the avant-garde in America. One of the most outstanding photographers of his day, Stieglitz was also a patron and mentor to important and innovative painters like John Marin, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, and Georgia O’Keeffe, many of whom became part of Mabel’s circle. She often visited Stieglitz who helped her “to See--both in art and in life.”

As one of the rebels of Greenwich Village, Mabel got involved with the Association of Artists and Sculptors that sponsored the Armory Show, the first exhibition of post-impressionist art shown in the United States. She promoted the show for a month before its opening on February 17, 1913, and felt like the exhibition was hers. She wrote: “It became, overnight, my own little Revolution. I was going to dynamite New York and nothing would stop me.”

By now thoroughly immersed in America’s avant garde, Mabel wrote for such leading modernist literary and art magazines as The Dial and Alfred Stieglitz's Camera Work, the leftist journal The International, and The Masses. For a brief time Mabel worked as a syndicated columnist for the New York Journal. She doled out advice on topics ranging from making quilts to setting up lending libraries for paintings. Her columns, which also conveyed her understanding of subjects of interest to her like Freudian psychology and the mind cure, appeared on the editorial pages of newspapers with some of the largest circulations in the U. S.

Ever restless, Mabel began spending time in Provincetown where she met and married artist Maurice Sterne. Within weeks she sent him off to the West, to New Mexico, a place she had heard about from Leo Stein. Within weeks Sterne wrote her a letter that began “Dearest Girl--Do you want an object in life? Save the Indians, their art--culture--reveal it to the world!”

When Mabel arrived in Santa Fe, she found the atmosphere too confining and insisted that she and Sterne go to Taos. She felt an immediate attraction: “My world broke in two right then, and I entered into the second half, a new world.” Mabel rented a place in January 1918. Drawn to Taos Pueblo, within weeks she met and fell in love with Antonio Luhan, a Taos Pueblo Indian. In a dream Mabel had before arriving in Taos, she had seen Sterne’s face turn into that of an Indian. The dream proved prophetic: Tony replaced Maurice in her affections. (Mabel sent Maurice back to New York, and in 1923 married Tony, her fourth and final husband.) In May 1918 Tony encouraged Mabel to buy 12 acres of beautiful meadow land. By the following year he had designed and helped build a four-room adobe which over time expanded to seventeen rooms.

Now ready to receive visitors, Mabel welcomed the first of her many famous guests, writer and activist Mary Austin in March 1919. Some of the others who stayed at the Mabel Dodge House included painters, sculptors and photographers John Marin, Georgia O’Keeffe, Ansel Adams and Laura Gilpin; dance choreographer Martha Graham; anthropologists John Collier and Elsie Clews Parsons, and writers Willa Cather, Aldous Huxley, and D. H. Lawrence.

Now ready to receive visitors, Mabel welcomed the first of her many famous guests, writer and activist Mary Austin in March 1919. Some of the others who stayed at the Mabel Dodge House included painters, sculptors and photographers John Marin, Georgia O’Keeffe, Ansel Adams and Laura Gilpin; dance choreographer Martha Graham; anthropologists John Collier and Elsie Clews Parsons, and writers Willa Cather, Aldous Huxley, and D. H. Lawrence.

Mabel had “willed” Lawrence to New Mexico long before she sent him a formal invitation to be her guest in 1921. She dreamed of establishing Taos as the birthplace for a new American civilization, one not based on getting and spending, or on the redistribution of wealth. Mabel thought that Lawrence was the “only one who can really see this Taos country and the Indians, and who can describe it so that it is as much alive between the covers of a book as it is in reality.” She told him about Taos and the Pueblo Indians, about Tony Lujan and herself, and relayed how much she wanted him "to come and know the country before it became exploited and spoiled.” Although he never wrote the book that Mabel envisioned, Lawrence did some of his best writing while living in New Mexico. The essays, poems and books he wrote (based on time spent primarily in the Taos area from September 1922 to September 1925) spoke to the mysticism of the place.

For Lawrence as for most of Mabel’s visitors, the Luhan home was a physical and spiritual oasis. Whether they established themselves permanently in northern New Mexico, or returned to the East and West coasts, they typically left Taos with their social ideals, their art, and themselves revitalized. Lawrence expressed this when he wrote: “I think New Mexico was the greatest experience from the outside world that I have ever had. It certainly changed me forever.”

Lawrence’s presence in her life changed Mabel forever. In 1932 Taos made literary news following publication of Lorenzo in Taos, her memories of D. H. Lawrence in New Mexico. The book increased Mabel’s national notoriety. A year later, Mabel issued the first volume of her memoirs. She had sent manuscripts of her autobiography to Lawrence. In the months before his death he read and commented on her work, calling it “the most serious ‘confession’ that ever came out of America, and perhaps the most heart-destroying revelation of the American life-process that ever has or will be produced.”

Despite negative criticism from the eastern literary establishment, Lawrence’s encouragement prevailed. Mabel published the remaining three volumes in the Intimate Memories series: European Experiences (1935), Movers and Shakers (1936), and Edge of Taos Desert (1937). She also wrote Winter in Taos (1935) and Taos and Its Artists (1947), a leading overview of the painters and sculptors from the art colony founders through the modernists of the 1940s. Up through the early 1950s Mabel continued to produce the occasional newspaper and magazine article, many dedicated to the history and culture of Taos.

Mabel died in 1962 leaving quite a legacy: her books, her home, and her spirit. Writer Spud Johnson perhaps said it best when he called her “a Southwestern institution.”

By Elizabeth Cunningham, 2011

Blog host, “Mabel Dodge Luhan and the Remarkable Women of Taos”