Eva Mirabal (Eah Ha Wa)

Eva Mirabal (Eah Ha Wa) had the ability to translate everyday events into scenes of warmth and seminaturalistic beauty. She was an unintentional portraitist, achieving character with a few deft lines. In miniature pattern, she was exceedingly skilled. Animals, genre, and the less formal ceremonials were her favorite subjects.

Dorothy Dunn, American Indian Painting (1968)

Born on ancestral land at Taos Pueblo, Eva Mirabal was called, Eah Ha Wa, which means Fast Growing Corn in the Tiwa language. Through visitors to the small village and the interrationships with the different cultures in the Taos community, young Eva learned of a world beyond the Pueblo. Her parents had sat as models for such European-trained artists as the Russian painter Nicolai Fechin and painter and printmaker Joseph Imhof. Their paintings and prints evidently influenced Eva early on. She made her debut as an artist at age 10 when a Chicago art gallery included her work in an exhibition.

Born on ancestral land at Taos Pueblo, Eva Mirabal was called, Eah Ha Wa, which means Fast Growing Corn in the Tiwa language. Through visitors to the small village and the interrationships with the different cultures in the Taos community, young Eva learned of a world beyond the Pueblo. Her parents had sat as models for such European-trained artists as the Russian painter Nicolai Fechin and painter and printmaker Joseph Imhof. Their paintings and prints evidently influenced Eva early on. She made her debut as an artist at age 10 when a Chicago art gallery included her work in an exhibition.

In the mid-1930s Eva began studying art at the Santa Fe Indian School. Dorothy Dunn, the director of art education, had opened The Studio School in fall 1932. It was the first institution to emphasize painting studies for Indian students. Trained in art education at the Art Institute of Chicago, Dunn taught the basic fundamentals of painting. She advocated the “Studio Style” of painting, a flat style similar to the “Oriental” works by Japanese printmakers. Dunn drew her inspiration from the early 20th-century San Ildefonso painters as LIKE Julian Martinez and Alfonso Roybal. The way they painted became the style of painting that she advocated. Using gouache (opaque watercolors) or tempera, her students learned to paint flat areas of color outlined or defined by a darker tone. Dunn promoted subject matter derived from her students’ cultural traditions, and encouraged them to utilize designs from the Pueblo murals and pottery painting, Plains hide paintings and rock art of their ancestors.

In her book American Indian Painting, Dunn noted that the woodlands and mountain rivers surrounding Taos Pueblo produced paintings that differed in theme from the environment of villages located to the south. She noted how two painters—Pop Chalee and Eva Mirabal—incorporated their native forests and mountains in their paintings. These two artists Dunn considered the most outstanding for their distinctive styles. (Dunn also noted that other women painters from Taos Pueblo-- Tonita Lujan, Jerry Lucero, Eloisa Bernal, and Rita Martinez—were developing styles of their own.) Pop specialized in “minutely decorative woodland scenes” while Eva tended to favor painting the daily life of Taos Pueblo’s inhabitants. In some paintings, Eva featured women in their historic traditional everyday dress: a manta (brightly colored shawl), turquoise beads, and over-the-knee white deerskin leggings. She paid close attention to details and captured intricate designs in clothing and in utility ware like baskets used in food preparation.

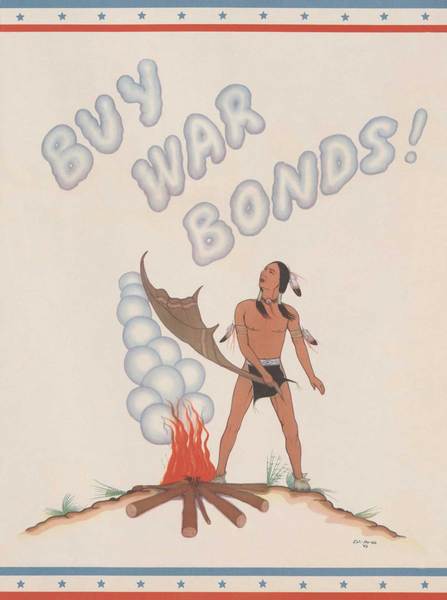

World War II interrupted Eva’s art studies. Like many other Indian people, she signed up for duty. On May 6, 1943 Eva enlisted in the Women’s Army Corps. She was stationed at Wright Field in Ohio. Her artistic abilities landed her an assignment as a cartoonist. Her “G.I. Gertie” series appeared in Corps publications, distinguishing her as the first published Native American female cartoonist (and one of the earliest American women to have her own cartoon strip.) While at the Santa Fe Indian School, Eva had learned to paint murals. This experience led to her next job. As assistant to Sgt. Stuyvesant Van Veen, she helped create a building-sized mural titled A Bridge of Wings at the world headquarters of the Air Service Command at Patterson Field, Ohio.

World War II interrupted Eva’s art studies. Like many other Indian people, she signed up for duty. On May 6, 1943 Eva enlisted in the Women’s Army Corps. She was stationed at Wright Field in Ohio. Her artistic abilities landed her an assignment as a cartoonist. Her “G.I. Gertie” series appeared in Corps publications, distinguishing her as the first published Native American female cartoonist (and one of the earliest American women to have her own cartoon strip.) While at the Santa Fe Indian School, Eva had learned to paint murals. This experience led to her next job. As assistant to Sgt. Stuyvesant Van Veen, she helped create a building-sized mural titled A Bridge of Wings at the world headquarters of the Air Service Command at Patterson Field, Ohio.

After the war Eva spent the academic year 1946-47 at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, studying and teaching as artist-in-residence. Then in 1949 she returned home and under the G. I. Bill studied at Taos Valley Art School run by the husband-wife artist team Louis Ribak and Beatrice Mandelman. By that time her career as an artist had blossomed. In 1946 Eva was the only woman who entered a painting in the First National Exhibition of Indian Painting at the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma. She subsequently won the Margretta S. Dietrich Award for her painting Picking Wild Berries at the Museum of New Mexico. In 1953 Dorothy Dunn included this painting in her travelling exhibition, Contemporary American Indian Painting, which opened at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Eva’s experience as a muralist and her attention to detail and design skills garnered her other mural commissions, including Bridge of Wings for the Buhl Planetarium in Allegheny Square in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Running Horses in the library of the Veterans Hospital in Albuquerque.

Eva returned to Taos Pueblo where she lived for the rest of her life. She immersed herself in communal life and participated frequently in ritual dances at the Pueblo. She painted the life she lived, through a series of paintings depicting individuals participating in the traditional rituals of daily life. Her paintings live on as record of her life at the Pueblo and a testimony to her skill as an artist.

In 2013 the Harwood Museum of Art will host a two-person exhibition of paintings by Eva Mirabal and her son, Jonathan Warm Day.

By Elizabeth Cunningham, 2011

Blog host, “Mabel Dodge Luhan and the Remarkable Women of Taos”

Photo and war bond poster image: The Eva Mirabal Collection, courtesy of Jonathan Warm Day and Christopher Gomez