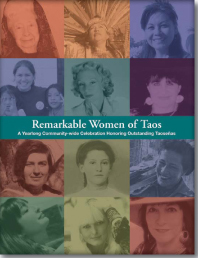

Dorothy Eugenie Brett

This British-American painter was born into an aristocratic family. She associated with such notables as Virginia Woolf, Katherine Mansfield, Aldous Huxley, Gilbert Cannan and fellow painter Dora Carrington. In 1924 "Brett", as she was known, moved to the D. H. Lawrence Ranch near Taos, New Mexico with Lawrence and his wife Frieda. She settled permanently in Taos, and became a United States citizen in 1938. This interview was channeled ‘in her voice’ by her biographer, Pamela Hall Evans.

I am grateful to be chosen to be honored as among the Remarkable Women of Taos and Northern New Mexico. Mabel’s house (Mabel Dodge Luhan) was always a haven, both for the struggling artist, and the successful. In my early Taos years, I lived at Mabel’s off and on. Even put in a bathroom, at my own expense, in one of the places she rented to me. I didn’t stay long---we had terrible arguments about my dog, who admittedly did bark at everyone who came into the courtyard. Well, that was a long time ago.

I am grateful to be chosen to be honored as among the Remarkable Women of Taos and Northern New Mexico. Mabel’s house (Mabel Dodge Luhan) was always a haven, both for the struggling artist, and the successful. In my early Taos years, I lived at Mabel’s off and on. Even put in a bathroom, at my own expense, in one of the places she rented to me. I didn’t stay long---we had terrible arguments about my dog, who admittedly did bark at everyone who came into the courtyard. Well, that was a long time ago.

First, I don’t portray Indians, many of whom are friends for over fifty years, as “noble savages,” though I’ve been accused of that. I don’t see them as lively subjects for magazine covers or advertisements. I attempt to paint their inner as well as outer selves; thus, my painting and my vision of the Indians has been trusted and aided, particularly by the Taos Pueblo Indians, for lo these many years.

Painting, to me, should inspire something of the beauty of life in the viewer. I understand that modern painters are testing their abilities and trying to express their feelings about modern life, but their work often feels hopeless to me, makes me want to jump into the closet and hide. So I aim to express hope, and beauty and something of love. For instance, when I paint a portrait, I don’t try to make a photographic representation of the person. That’s what cameras are for! Instead, I am fascinated by the personality, the energy, the uniqueness of the person, the parts that one can’t necessarily see on the surface, but which animate the life, make the life interesting and worth putting on canvas.

You’ve asked what my goals are for the future. Well, I’m an old lady now, so I suppose I just want to go on painting as long as possible. My primary subject matter will continue to be the Indians and landscape around me, but for the last several years, I’ve been reaching for a more spiritual character in my work. If “spiritual” is the right word. Connected is maybe a better one. Yes. I’m trying to demonstrate how everything is connected: people, animals, earth, sky. I’m a kind of evangelist, I suppose. I’m always trying to get people to see the good in life, the beauty in people and their surroundings, and how, no matter all the evil that people do, we cannot disconnect ourselves from one another nor from the earth. This is something the Indians have taught me, for which I am thankful.

Oh, young people ask me all the time how I came to be an “accomplished” artist. I tell them three things: get rid of fear, always work harder than you think yourself capable of doing, and work every day. This goes for painters, writers, musicians, what have you. I never go anywhere without a camera or sketchbook, and have found that for me, being deaf is an aid to my work. I can turn off my hearing device and focus my eyes, my brain, my whole self on seeing what is in front of me, without distractions like conversations, excitements, or other enticements that may be around me. But not everyone is deaf, so I just tell people to work, to not assume you’ll be a success, and to move forward as if your very next bite depended on every brush-stroke or pen-stroke.

Several people have been inspirational to me, each for different reasons, a few for similar reasons. First was my father, Reginald Viscount Esher (pronounced EE-sher…Americans always want to call him after the letter S). He was a man born to limited privilege, who always carried himself like a Duke or a Prince, believed in his abilities, and was friendly to everyone as an equal. There were some not-so-admirable things about my father, but among his best qualities were his abilities to work intensely, always completing what he started, and to charm anyone he met by putting them at ease, displaying interest in them, and leaving them feeling particularly chosen for his attention. In other words, he taught me not to be a snob, to work hard and well on every project, and to treat well and kindly those around one. I think I’ve accomplished the second lesson, but will probably still be working on the first and third till I drop!

Katherine Mansfield challenged me to work hard, to throw myself into painting, no matter how unsuccessful I may have felt my efforts to be. D.H. Lawrence also challenged me to work hard, not to be afraid of any kind of work, from cleaning acequias to riding forty miles round-trip in a day for mail. He taught me to listen to my own voice, to be meticulous in recording what I hold in my head (my creative brain), and to love what I do, where I am, and who I choose to be with. He was a hard task-master, berating me when I shrank from work or got distracted by friends or social activities, and encouraging me in his belief in my talent. He also taught me that friendship can encompass all kinds of emotions, interactions, and responses. He was most concerned about my overcoming a general fear of life.

Then, of course, there was Mabel. Mabel was a force in my life for thirty years---Ha! She was a force in Taos life for far longer. She could be such a thorn in one’s side, but when she was ON one’s side, there was no better, stronger ally. If she supported one, she did it one hundred per cent and never gave up on one. Her judgment of people’s talent was remarkable, never mind that she sometimes got a bit too involved with “making” someone a success. She understood before anyone else did what I was trying to do in my paintings of Indian life and championed that effort. It was she who took me to New York to meet Alfred Stieglitz. Between Mabel and Stieglitz, by 1930 I was bucked up enough to propose, all on my own, that I paint Leopold Stokowski’s portrait. You know, the renowned conductor of the Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra. The painting of his portrait, not once, but sixteen times, was a milestone in my career…..not because the paintings were popular and made me rich (neither thing happened; Mabel, herself, didn’t even like them) but because I saw for the first time that I was capable of doing even more with my talent than what I’d previously believed. Mabel is the one to thank for this enlarged view of my work because without her, I’d never have had the courage to approach the New York art market, never have met Georgia O’Keeffe who is the only pure painter I’ve ever known, and never have had the experience of working and becoming friends with both Stieglitz and Stokowski.

You know, I came to Taos with D. H. Lawrence and Frieda as an escape. My English life had become so tangled in grief, rebellion, poor judgment, and disappointment that Lawrence’s invitation to spend six months away, in “Mexico,” as we called it, seemed my only hope of renewal. I felt like a chance to start fresh, become the person I’d always meant to be. I know other women who have come to Taos for similar reasons, but primarily to begin anew. They, as I did, left behind whole other lives in order to create spanking new ones here.

I’ve actually thought about moving to other places at different times in the last fifty years. I’d traveled in Italy and France and liked both. I liked Jamaica enormously, and would have liked very much to see and live in India for a while. But Taos always drew me home. It’s been a combination of things that kept me here. People, of course. There’s an enormous tolerance here for the oddities of artists and their ways. And people are friendly. Anglos, most of whom come from somewhere else, and are looking for friends and a way to feel at home. The Indians are more cautious about making friends with Anglos, not untrusting, but more shy, I’d say. They aren’t out-going like most Anglos, so they take their time about getting to know someone, coming at a friendship in an oblique manner. I always appreciated this approach, being a shy person myself.

Aside from the people, I’d say that the physical beauty of the Taos area is like a drug. Beauty has always been an important element in how I think of and respond to life—I learned from my father that beauty is one of life’s great blessings. But the beauty of Taos---I think I must be addicted to it. When I go away from here (well, not so often any more) I long for the place, pine for the way it looks and feels and smells and, yes, tastes. Naturally, there is the sky, impossible to paint. No one has really ever gotten it right. It’s too clear, like looking through turquoise glass. And then there are the vistas. To be able to see so very far, in this thin, dry air is almost magical, especially for someone like me who comes from the foggiest, rainiest, dampest country in the Northern Hemisphere! For me, since I hear so little, seeing is just about everything. Taos is a place for seers, for visual folk. I think some people view it as a place for Seers and Visionaries, and I suppose that may be true. For me it’s a place where inner vision is prompted by viewing the outer landscape. Not many destinations have such a strong sense of place as Taos---for some that includes its history but for me, it’s the raw incandescence of the place: the glitter of sand in the air during one of those blood-orange sunsets, or the startling weight of the desert silence, undisturbed by any animal or breeze or human sound. It’s double and triple rainbows after a thunderstorm that sounded, at its loudest, like a bad theatrical effect, or snow, pure white, falling, spinning, drifting and piling-- cleansing on a winter’s afternoon. Asters and sunflowers blooming together on September roadsides that lead up the mountains into the astringent yellow of Autumn’s aspen trees. In the midst of all this beauty, the Indians move with graceful elegance and delicate understanding of their connection to and dependence on this unique land. Why would I ever live elsewhere?

Aside from the people, I’d say that the physical beauty of the Taos area is like a drug. Beauty has always been an important element in how I think of and respond to life—I learned from my father that beauty is one of life’s great blessings. But the beauty of Taos---I think I must be addicted to it. When I go away from here (well, not so often any more) I long for the place, pine for the way it looks and feels and smells and, yes, tastes. Naturally, there is the sky, impossible to paint. No one has really ever gotten it right. It’s too clear, like looking through turquoise glass. And then there are the vistas. To be able to see so very far, in this thin, dry air is almost magical, especially for someone like me who comes from the foggiest, rainiest, dampest country in the Northern Hemisphere! For me, since I hear so little, seeing is just about everything. Taos is a place for seers, for visual folk. I think some people view it as a place for Seers and Visionaries, and I suppose that may be true. For me it’s a place where inner vision is prompted by viewing the outer landscape. Not many destinations have such a strong sense of place as Taos---for some that includes its history but for me, it’s the raw incandescence of the place: the glitter of sand in the air during one of those blood-orange sunsets, or the startling weight of the desert silence, undisturbed by any animal or breeze or human sound. It’s double and triple rainbows after a thunderstorm that sounded, at its loudest, like a bad theatrical effect, or snow, pure white, falling, spinning, drifting and piling-- cleansing on a winter’s afternoon. Asters and sunflowers blooming together on September roadsides that lead up the mountains into the astringent yellow of Autumn’s aspen trees. In the midst of all this beauty, the Indians move with graceful elegance and delicate understanding of their connection to and dependence on this unique land. Why would I ever live elsewhere?

Still, I do know why women, especially, continue to come to Taos. Or think I do. There is a feminine quality to this place. While other places are also beautiful, the feminine holds sway here. An opposite example would be the Grand Canyon, which is definitely and resoundingly masculine. There is a gentle, delicate air about Taos, an atmosphere of coming home, of acceptance. Taos isn’t perfect though. Like any small town, it’s a gossip mill and a generator of personality conflicts. But when people look UP, OUT of themselves, what they see is as near to sacred as I can imagine a place to be. There is a serenity in its beauty, a generosity and openness, and something nurturing too. Maybe how I feel about it is related to the encompassing mass of Taos mountain at one’s back while before one, everything opens out, to the West, tumbling from the bounty of the mountain, across the lush valley floor, and on across the gorge of the Rio Grande River onto the flat, shimmering mesa that falls away towards Arizona and the desert. Everything about Taos seems to me to speak of promise and hope. I believe that one would have to be blind AND deaf, without the sense of smell or taste or touch, not to respond to this place. I keep hearing with my inner ear its constant call for me to do my best, to not give up, to try once more to try to see beneath the surface of life. I don’t know how else to explain my response to Taos.

As for cultivating remarkability, I can only say that with so many talented people flocking here, and then helping one another, there are bound to be some remarkable women emerge from the group. Support. Mentors. Patronage. Call it whatever you like, there are a lot of folk in Taos who see the value of art in all its forms, who are always to be counted on for support of some kind. And there are a lot of artists who aren’t jealous or over-protective of their talents…they have no difficulty helping, guiding others. Of course there are some of the other kind, but not so many. The atmosphere around art, in particular, in Taos is one of “Show us what you can do, and if there is talent there, we will help you grow it.” Are women better at this than men? Yes, I think so. But, I’m no expert. Besides, I had Mabel, and later John Manchester (a good man with many of the same feminine qualities that Lawrence had) to boost me up. So maybe it’s not being a woman but being open to one’s feminine side that makes one a better mentor or supporter of women in public.

My favorite places in Taos? Well, there have been many over the years, and I’m a bit limited now as to where I go, especially alone. But I’ll give you a little list of places that have touched me over the years if you like.

• Camping in the mountains with Trinidad, Mabel, and other friends. I liked the smell of the pines, the surreal color and setting of the lake, and the “sound” of the horses’ hooves on the forest floor…it’s a sound I could feel in my body.

• Taos Pueblo for any ceremonial dance. I like it in the summer, sitting on the sun-heated rooftops, watching the dancers weave and sway as the drumbeats ‘ vibrations travel through the ground and the walls of the houses up into my body. I like it in the winter when no amount of clothing keeps one warm and snow covers everything, while the Indians are dressed in skins, bare shoulders and legs, bells and feathers, dancing in gratitude and wonder at what Nature has provided to them. I like the way the adobe walls of the houses change color in shifting light and seasons, the way the stream bubbles and curls its way through the village, the laughter and chatter of the women as they move about their work, never failing to hail me when I am there.

• The view from behind Mabel’s house, up to Taos Mountain (visible from the back of the Mabel Dodge Luhan House). It seems to loom over the valley in a way that some might call malevolent, but which I’ve always felt was protective. The meadows there are always green early in Spring, and stay that way long into Fall. They are quiet, full of ground-nesting birds and small critters, sometimes deer that don’t know how dangerous it is to come that close to town, and horses---lithe, sleek, Indian horses that stroll through the tall grass, munching, switching their tails, sniffing the air, coming together for a “chat” and a nose nuzzle.

• The Rio Grande Gorge. Saki Karavas [deceased owner of the present La Fonda Hotel] parks on the side of the road and I walk with my sweet little dachshund (named Little Reggie, after my father!) to peer into the gash in the earth. I enjoy the sound of the river as it roars through the bottom of the gorge, especially in the spring when the snowmelt crashes out of the mountains and rushes beneath me, leaving spray and rainbows for my pleasure. A trip out there also reminds me of all the happy afternoons I have spent fishing in the Rio Grande, well south of here, of course. Hours of sun and concentration, hope for a bite, expectation of a delicious fish fry-up for dinner, disappointment on days when there were no bites and the thrill of days when everything bit and there was fish to share among friends in town and at the Pueblo.

I hope my answers will be useful to you. I’m old now and often find the past more interesting than the present. But I can see that you want to invite others to see and understand why people like me come to Taos, make it home and the base for a career of one kind or another. But I have to say I do admire what you are doing for young women. Just don’t forget to tell them that the very best thing they can do for themselves is to CUT OUT FEAR. Then they will be fine.

Dorothy E. Brett

P.S. Please, don’t refer to me as Lady Brett. In England I’m Hon. DEB, but that’s only because of my birth. Here, where I’m an American, I’m just Brett.

Author: Pamela Hall Evans, 2011

Pamela Hall Evans’ biography on Brett is in progress. She hopes to publish her book,

tentatively titled Cut Out Fear: The Life of the Artist Dorothy E. Brett, soon.

Painting of Dorothy Brett by Robert Ray, from the Harwood Museum of Art collection.