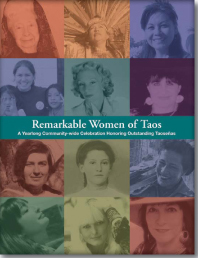

Lydia Garcia, Santera

The flourishing tradition of New Mexico Hispanic vernacular art began toward the end of the eighteenth century when the New Mexican artisans imitated to the best of their abilities the statues, paintings, and popular prints imported from the South. The people of New Mexico demanded art that was real. To them, art was part of the religious domain; art participated in the very being, in both the essence and the existence, of one or another of the heavenly persons: God and His angels and saints. In this sense, a Santo is holy art because it was fashioned according to a holy prototype and for a holy purpose. – Thomas J. Steele, S. J. in Santos and Saints: The Religious Folk Art of Hispanic New Mexico

Lydia Garcia never dreamed that she would become a santera or painter of saints. In her youth, she like her family and neighbors, considered the santos (images of saints) that adorned the family altar part of their religious devotion. Only later did hand-painted retablos (wooden panels) and hand-carved bultos (carved figures) become regarded as art separate from the faith that sustained the lives of Hispanic New Mexicans. As Lydia puts it: “It wasn’t art then, it was more of a prayer.” She remembers that her father, Guadalupe Elias Vigil, made crosses or painted small images of saints to give friends and family members on special occasions or in times of need. From him Lydia learned to paint and carve wood and to formulate paint colors using roots and berries. Elias jokingly referred to his eldest daughter as “Daddy’s boy” because she learned to chop wood and she accompanied him on remodeling jobs. From working with adobe and doing carpentry work, Lydia became skilled with her hands. From her mother, Maria Ines, Lydia learned to cook and tend the garden. As a small child, she watched her mother do colcha embroidery.

Lydia Garcia never dreamed that she would become a santera or painter of saints. In her youth, she like her family and neighbors, considered the santos (images of saints) that adorned the family altar part of their religious devotion. Only later did hand-painted retablos (wooden panels) and hand-carved bultos (carved figures) become regarded as art separate from the faith that sustained the lives of Hispanic New Mexicans. As Lydia puts it: “It wasn’t art then, it was more of a prayer.” She remembers that her father, Guadalupe Elias Vigil, made crosses or painted small images of saints to give friends and family members on special occasions or in times of need. From him Lydia learned to paint and carve wood and to formulate paint colors using roots and berries. Elias jokingly referred to his eldest daughter as “Daddy’s boy” because she learned to chop wood and she accompanied him on remodeling jobs. From working with adobe and doing carpentry work, Lydia became skilled with her hands. From her mother, Maria Ines, Lydia learned to cook and tend the garden. As a small child, she watched her mother do colcha embroidery.

At that time Talpa, a small community outside Taos, was isolated. This and more affordable land drew artists to the area. When painters Ward Lockwood and Andrew Dasburg purchased homes in Talpa, they hired Lydia’s father to build additions onto their homes. Lydia had already started painting by then, adding decorative elements like pigs and chickens to the trasteros (cupboards) made by her father. The family’s acquaintanceship with the two artists eventually led Lydia to their studios. In recognition of her talent, Lockwood gave her old brushes and tubes of paint. Another kind of support came from Dasburg. If she was “very quiet” as the artist requested, she could watch him paint. For hours Lydia sat and observed how he developed a painting and how he made the familiar landscapes around Talpa and neighboring Ranchos de Taos come to life on the canvas. It was magical! Another artistic influence came from the works of the great early 19th-century New Mexico santero, Antonio Molleno. Lydia saw the reredos (altar screens) he painted at least once a week when the family attended services at San Francisco de Asis church. Despite all these influences, becoming an artist was not on her horizon.

Just after Lydia graduated from sixth grade, her mother became ill and Lydia left school to help support her family. At age sixteen she married and went to live in San Antonio, Texas. When that marriage ended, Lydia returned to Taos and married again. Ten months later her second husband died. She married for a third time, then separated. Faced with being financially responsible for her five children and later her parents, Lydia attended beauty school. She opened her own business and worked as a professional hair stylist for 18 years.

During this time, Lydia continued to carve and paint. As her father had done, she gave her santos to family and friends. Then, when her oldest son was attending law school in Salt Lake City, he called her to say “Momma, I hope you don’t get upset with me but I sold all of your art pieces that I had. I did this because I needed the money to have my teeth worked on.” Lydia’s response was “Praise the Lord!” She had never in her wildest imagination thought that “people would actually pay money for my art.” That happened in mid-1960s. From then on Lydia’s art began to sell. With this success, she entertained taking art classes. One day she saw an ad for an art course that Taos painter Ray Vinella was offering. She took some of her work to him and told him she wanted to improve her skills. When Vinella saw her work he realized she had a special talent. He cautioned Lydia: “If you go ahead and take this course, you will lose this precious gift.” Lydia took his advice and has been painting in her own style ever since.

In the 1970s when Lydia found it too difficult to get involved with Spanish Market as an outlet for her work, renowned Taos artists Larry Bell and Jim Wagner encouraged her to open a studio in her home. At home she could both create and sell her work. She opened Galleria Elias y Ines (named for her beloved parents) in the house and workspace built by her grandfather. Soon she had “many people coming here and more work than I thought possible.” Instead of exhibiting her work, she built up gallery representation in Texas, Tennessee, and other states as well as in Taos. The Millicent Rogers Museum gave her a solo show in 2000. Museums and private collections worldwide own her retablos and santos, and churches have commissioned altarpieces.

St. John Baptizing Jesus (1999)*

Lydia adapted her Catholic upbringing to her art. She draws on her New Mexico Hispanic heritage, which includes a personal “familial” relationship with the Virgin Mary, Jesus, and the angels and saints. In childhood Lydia’s father had read “a lot of scripture” to his five daughters. After he finished reading, he asked them to write little stories giving their interpretations of what they had heard. Lydia developed her own stories and prayers based on themes from the Bible and on the Catholic religious practice of asking for the help of saints. Not only does she see her talent as God’s blessing and her art as devotion, Lydia also imbues her work with prayer. When a piece is finished, she signs it and often pens a short explanation or prayer. On the reverse side of her retablos, for example, she might write a supplication like “O Lord, let me not be afraid to ask for help.” In this way she passes on her life’s blessings to others.

Her traditional faith in God, her spirituality, and her vibrant depiction of saints places Lydia in the lineage of New Mexico’s centuries-old santero tradition. She once stated: “When Hispanics came they brought the images and religion in their hearts. They used what was in the area, which was wood. I continue to work in this tradition.” Trained by her father to be resourceful and conscientious, Lydia also uses the materials at hand. These include recycled wood, tin cans, old furniture and other discarded items or treasures left outside her home by friends and neighbors. Recycling these materials by using them in her art is Lydia’s contribution to a greener world.

Taught by the example of her father to serve people in the community, Lydia also reached out. She taught at the Taos Institute of Art for 15 years. Recently she has helped with children’s art programs at the Millicent Rogers Museum. As she did with her own children and grandchildren, Lydia guides the little ones and encourages them to find their own creative expression. She also helped bring art to the children of Taos by publishing a coloring book, Color with Your Heart with the Colors of God. Lydia also shared her talents outside Taos, traveling to Colorado and to Indiana to give workshops. On three separate occasions the Hispanic Cultural Center and the Alaska Council of Art invited Lydia to Anchorage to conduct courses on the use of recycled materials in creating art. For years she shared her musical talent, playing the guitar at early Sunday mass at the San Francisco de Asis church. Throughout her life in the quiet time before dawn, the hour when the spirit is upon her, Lydia prays and plays her guitar before she commends herself to her painting. This spirit that moves her is encapsulated in her words: "All work is created with love and prayers. All my work is in prayer to know my Jesus--that I give witness for my God. That I will serve him with pure love, for his love for me."

Asked what she wanted to accomplish with her art, Lydia would like it to touch other people’s spirits as it has touched hers. And what is important to Lydia about her work? “It gives me satisfaction beyond words.” She adds, “Every day is a celebration. I love what I do.”

By Elizabeth Cunningham

Blog host, “Mabel Dodge Luhan and the Remarkable Women of Taos”

Photos courtesy of the Millicent Rogers Museum. Appreciation to Carmela Quinto.

Photo at top: Lydia teaching retablo making at the Millicent Rogers Museum

* Lydia’s retablo titled St. John Baptizing Jesus (1999) is made of recycled wood painted with acrylic paints. It measures 27"h x 32"w and is in the collection of the Millicent Rogers Museum, MRM 2000.003.001. Lydia wrote the following words on the back: "John Baptizing Jesus: Father Bless me with the holy water when I was baptized. Amen"