Taos Pueblo Potters

Sharon Dry Flower Reyna, Jeralyn Lujan Lucero

Three Generations in Clay: Jeri Track, Juanita DuBray, Bernadette Track, Soge Track, Dawning Pollen Shorty and Dakota Concha

Taos Pueblo is known for its micaceous pottery which dates back five hundred years. While there are many women artists from Taos Pueblo, it seemed fitting to introduce those who work in this ancient medium. As you will see, these potters, representative of numerous other Taos Pueblo women, have many other talents.

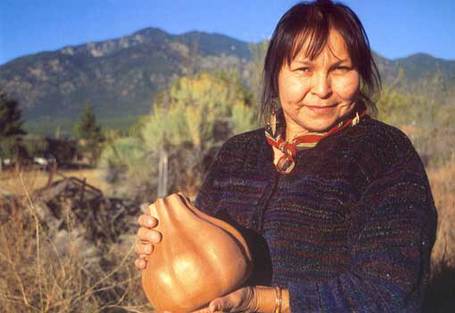

Sharon Dry Flower Reyna, Traditional Contemporary Clay Artist

The clay has taught me to be patient, to grow, to respect what was given to me and what I can give back. It has brought me livelihood, it has brought richness to my life. Sharon Dry Flower Reyna quoted in All That Glitters: The Emergence of Micaceous Art Pottery in Northern New Mexico by Duane Anderson.

The clay has taught me to be patient, to grow, to respect what was given to me and what I can give back. It has brought me livelihood, it has brought richness to my life. Sharon Dry Flower Reyna quoted in All That Glitters: The Emergence of Micaceous Art Pottery in Northern New Mexico by Duane Anderson.

The clay came to Sharon Dry Flower Reyna in childhood. She descends from a lineage of potters including her grandmother Ursula Mirabal and Virginia T. Romero, who Sharon considers “the Matriarch of Taos potters.” The second of four daughters born to Reycita Mirabal Reyna and Mike Redshirt Reyna, she has girlhood memories of her elders (potters at Taos Pueblo were traditionally women) giving her pieces of clay to occupy her little hands. In her early 20s Sharon became more formally acquainted with the medium in her studies in Los Angeles with African American potter Manuel Davis, where she was introduced to cross-cultural ceramic techniques and styles. Back at Taos Pueblo, Sharon Dry Flower discovered a container of micaceous clay and two black polishing stones left after her grandmother’s death. “At that moment I made a commitment to Mother Clay.” With no family elder to guide her, she asked other Taos Pueblo potters to teach her about where to find and dig clay and how to process it. Sharon Dry Flower launched her artistic career from her home in 1970 while caring for her infant son. She used the same traditional method as generations before her, building her pots from coils of clay. As soon as they dried, Sharon Dry Flower pit fired them using cottonwood bark. She started with utilitarian ware: cups, dishes, cooking pots, water jars. As Sharon Dry Flower tells it, “As soon as I picked up the feel of the clay and mastered the traditional styles of Taos Pueblo, I wished to turn it into something cool, something jazzy.” She started thinking outside the box. Ever questing after new artistic expression, she explored the possibilities of clay through more sculptural pieces.

After earning a degree in museum studies and three-dimensional art at the Institute of American Indian Art in 1987, Sharon Dry Flower experimented with new techniques. By combining the double firing method of Japanese Raku with micaceous slips, she developed her signature “micaceous Raku” pottery. Today she is known both for her pottery and clay sculpture. Her figurative works of blanketed Indian people happened by accident. When a pot she was working on didn’t turn out well, Sharon Dry Flower cut it in half. The wet clay collapsed upon itself leaving what looked like a shawl. She molded the piece into a form, then fired it. What emerged was a figure that looked like an elderly woman with a primitive face. The series of work that emerged came about by accident, part of Sharon Dry Flower’s life philosophy: “I stay open to accident, allowing the moment to happen while I stay in the moment.” Sharon Dry Flower continued to make sculptural figures out of clay. She also learned metal work and cast some of her work in bronze. For the last two years she has worked with and won awards for her fused glass.

Noted for her innovation within tradition, Sharon Dry Flower was one of ten micaceous clay masters featured in the book All That Glitters written by Duane Anderson and published by the School of American Research. In 1992 the Southern Plains Indian Museum and Crafts Center hosted a solo show with an accompanying exhibition catalog of Sharon Dry Flower’s work titled Creations from the Earth. She had another one-person exhibition at the Albuquerque Museum. She was one of 38 Native artists from different tribes featured in Indian Humor, an exhibition that travelled to venues throughout the U. S. from 1995 to 1998. Sharon contributed several figures from her “Koshari Boy” series. One shows a tubby Pueblo clown eating a cheeseburger, another eats slices of watermelon. Of her Koshari Boy IV Sharon Dry Flower stated: "The Koshari's job is to bring humor, to teach and bless us with seasons. I am respectful of our sacred ways and things, but I can't help myself but to view Indian life in an off-the-wall kind of humor."

Sharon Dry Flower has shown widely and received high acclaim for her art including four awards at the Eiteljorg Indian Market and Fair as well as numerous honors at the Santa Fe Indian Market, the Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair and Market, Taos Invites Taos and other shows. Sharon Dry Flower’s work is in the collections of the Denver Museum of Natural History, the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art in Indianapolis, Museum of Indian Arts and Culture and the School of American Research in Santa Fe, and the Millicent Rogers Museum in Taos. Sharon Dry Flower has shared her expertise through classes in micaceous clay. After instructing at Pojaque Pueblo’s Poeh Center (established in 1988 for cultural preservation and revitalization within the Pueblo communities), she began teaching micaceous clay classes at Taos Pueblo. Students from all over the country benefitted from Sharon Dry Flower’s classes held for years at the Taos Institute of Arts. Looking back at her long involvement with clay, Sharon Dry Flower gives thanks: “You’re with the earth. She’s working with you. I think that’s pretty special.”

Jeralyn Lujan Lucero, Clay Sculptress, Painter, Gallery Owner

I am always searching for and learning new ways to strengthen and master the arts. I paint, sculpt, and make micaceous pottery and sculpt full human forms. Making silver and turquoise fingernails are my most recent artistic enterprise. And I am not dead yet, so working in bronze and stained glass is on my “to do” list.

I am always searching for and learning new ways to strengthen and master the arts. I paint, sculpt, and make micaceous pottery and sculpt full human forms. Making silver and turquoise fingernails are my most recent artistic enterprise. And I am not dead yet, so working in bronze and stained glass is on my “to do” list.

Since her parents Pauline and Jerry Lujan worked in Los Angeles, Jeralyn was born and grew up there. Her mother, who worked as a Registered Nurse at the Glendale’s Memorial Hospital, loved to travel. Jeralyn remembers family weekends spent at bullfights in Ensenada, Mexico, driving to beaches at La Jolla and Santa Monica or to the Monterey area to see the redwoods. Pauline loved to round dance and Jerry loved to sing, so the family traveled to attend West Coast powwows. The Lujans considered Los Angeles a place to work but Taos Pueblo was home. They returned there to live as soon as it became economically feasible.

Jeralyn’s life as an artist started when she attended the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe. When she applied for college there the Director Ramona Tse-Pe looked at Jeralyn’s portfolio and stated that she was overqualified but admitted her anyway. At the IAIA Jeralyn won every possible award for her art. Teachers and directors further complimented her by buying her work. Contact with Native students from over 100 nations across the country enriched Jeralyn’s experience at IAIA. She learned about other tribes and benefitted from the exchange of cultures. She remembers students in drawing classes posing for each other dressed in their Native attire.

Following graduation from IAIA, Jeralyn came home to Taos Pueblo and married James Cruz Lucero, a noted silversmith. As the mother of three children—Leon James, Pauline Faith, and Dylan—Jeralyn’s first priority is nurturing them on all levels to help them reach their fullest potential. For help with teaching her children Taos Pueblo ways, Jeralyn is guided by one of the matriarchs, her mother-in-law Tonita Lucero. She stressed the value of participation in tradition life: “You have to participate in order to learn. It’s a life long journey!”

Art is Jeralyn’s other journey. Singled out first as a potter by the Millicent Rogers Museum, she uses the same micaceous clay as her grandmother and great-grandmother did to make bean pots and household dishware. Jeralyn, however, carried the use beyond utilitarian ware. After mastering traditional forms, she created three-dimensional sculptures. She sculpted full human forms drawing on mythology and the rich cultural heritage of Taos Pueblo. Jeralyn is known for her storyteller and other micaceous sculptures. Looking inside some of her large-scale clay vessels it’s surprising to find fully sculpted corn maidens.

Jeralyn has won wide acclaim, not only for her micaceous clay works but also for her painting. She has exhibited in art fairs and festivals including the Eight Northern Indian Pueblos and the prestigious Southwestern Association for Indian Arts, which showcases artistic excellence. Several institutions have collected Jeralyn’s work, including the Museum of Red River in Idabel, Oklahoma, the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture,the School of American Research and the IAIA in Santa Fe, and the Millicent Rogers Museum in Taos. She and her micaceous pottery are featured in the book All that Glitters. Jeralyn’s two-dimensional work stands out. It has been compared to the painting of Pop Chalee, a famous Taos Pueblo woman artist. So it is no surprise that Jeralyn did the cover art for the renowned activist, author and lawyer Vine Deloria’s book, Spirit and Reason.

Over the last 23 years Jeralyn has operated her Sagebrush Deer Gallery at Taos Pueblo. It serves partially as her studio as does her kitchen table. Through her gallery Jeralyn has met people from all over. As she puts it “My work is all over the world and I have many local and foreign friends as far away as Russia.”

Jeralyn Lujan Lucero has a long list of favorite Taos places. Among them are Taos Pueblo and its San Geronimo church, the galleries owned and operated by her fellow artists and the Taos Pueblo Indian Horse Ranch. She also likes visiting the homes and studios of Taos Society of Artists members E. I. Couse and Joseph H. Sharp and the Millicent Rogers Museum. Besides Cids Food Market, Taos Mesa Brewing Company and the KTAO Solar Center, Jeralyn has two “musts”—the Barry Norris Studio and the Soap Emporium in El Prado. (Jeralyn did the cover design for packaging owner Michelle Lewis’s soap which Jeralyn also sells at her gallery along with her own special hand-made soap.) To see Jerilyn’s work, visit Taos Pueblo and Sagebrush Deer or contact her at 575 776 4686.

Three Generations of Contemporary Potters at Taos Pueblo

Sisters Jeri Track and Juanita DuBray; Jeri’s daughters, Bernadette Track and Soge Track; Bernadette’s daughter, Dawning Pollen Shorty, and Soge’s daughter, Dakota Star Concha

Left: Soge and Jeri Track (seated), Dakota Concha, Dakota’s daughter Reesa in foreground. Right: Bernadette Track, Juanita DuBray, Pollen Shorty

All of these women, descended from an unbroken line of Taos Pueblo people, grew up in their ancestral family complex in the traditional part of Taos Pueblo. Designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1992, two buildings—the North House and the South House, dating back to about 1350—constitutes one of the oldest continuously inhabited Pueblo structures in the United States. Today as in the past, homes there have no electricity, no indoor plumbing or running water. Like centuries of their predecessors, these women cooked over wood fires, hauled water for cooking from the Rio Pueblo, and lugged children and provisions up and down ladders to reach the North House’s upper stories.

From their mother Tonita Suazo, sisters Jeri and Juanita learned traditional women’s ways and about the preparation of traditional foods. At the kitchen table they also watched their mother making micaceous pottery for cooking and serving the family’s meals. Designated for home use, this cookware was never sold, although occasionally Tonita gave clay images she made that resembled their Taos Pueblo dwelling to friends.

Juanita DuBray

I pray before I do any work, centering myself spiritually, asking for power to be given to each new piece so that it will become a blessing to the person who owns it. – Juanita DuBray quoted in All That Glitters.

Of the sisters, Juanita DuBray made the first venture into earning a living from clay. While attending a boarding school in Albuquerque, she studied Art History and Native American Arts and History. In 1980, after a career as a pharmaceutical technician, she became interested in historical Taos Pueblo ceramics. She studied the traditional forms and design elements which included tool-impressed rims and loop handles. Juanita relates: “I began making pots using traditional designs and symbols. These pots were designed as one-of-a-kind, with ancient symbols being used in different ways on each piece.” Later, using micaceous and white clays, she created contemporary designs on traditional pots. Juanita developed her own patterns using lizard, turtle and corn motifs. In 1986 the "Corn Designs" came to her in a dream following the death of her daughter Nanette in a tragic motorcycle accident. “The Corn symbolizes my daughter's spirit and each Corn piece is infused with happiness, healing, love and beauty, which is passed on to those acquiring the pots.” Expanding on the storyteller forms pioneered in the 1960s by Cochiti potter Helen Cordero, Juanita makes “Storyteller Doll” figures which include mother and father storytellers and grandmother and grandfather storytellers. Whenever she gets a storyteller commission, she asks for the number of children or grandchildren, and includes the respective number in the piece. A prize-winning potter, Juanita has exhibited her work at the Renwick Gallery at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., the Heard Museum in Phoenix, the Museum of New Mexico, the Wheelwright Museum and the Institute of American Indian Art in Santa Fe, and at the Millicent Rogers Museum in Taos. She has also shown at Denver Indian Market, Santa Fe Indian Market, Eight Northern Pueblos Indian Market and Taos Invites Taos. Her pottery is housed in private collections in the United States, Germany and India, and in the permanent collections of the School of American Research in Santa Fe, the Holmes Museum of Anthropology at Wichita State University in Kansas, and the Millicent Rogers Museum. The School of American Research designated Juanita DuBray as one of ten Master Potters in the book All That Glitters, and invited her to attend the school’s Micaceous Pottery Artists Convocation. In 2004 Juanita taught micaceous pottery at the Taos Art School.

Jeri Track

New insights into pottery techniques came to the Track family through potter Mary Witkop who encouraged them to experiment and develop their own styles. Mary lived and worked in Pilar, New Mexico. In 1981 she began experimenting with micaceous clay collected in the Taos area. She also began working with Taos Pueblo potters including sisters Juanita DuBray and Jeri Track and Jeri’s daughters Bernadette and Soge. Mary learned from them how to prepare and work with the local clays. The potters exchanged ideas and techniques.

This was a starting point for Jeri Track’s career in clay. Influenced by her mother, Tonita Suazo, she is best known for her miniature Taos Pueblo pieces. Made of micaceous clay, she has her customers in mind when she creates them. Jeri wrote:

I talk to my little houses while I make them and tell them wherever you may end up, let us hope that you will be in a beautiful home with a wonderful family. The houses will bring a beautiful spirit in your home and bless your household. The chilis are real and hot and the firewood is cedar. The outside ovens are where we bake bread.

Along with this description, with her typical sense of humor, Jeri adds: “The little women are busy all the time because their men are out working - Maybe?"

In addition to making miniatures, Jeri taught week-long classes in micaceous clay methods at her Taos Pueblo home. Assisted by her daughter Bernadette, Jeri took students to an age-old site to dig their own clay in the mountains near Taos. Back at Jeri’s place, the students learned to process the clay: pounding it and adding water, then letting it dry in the sun. They learned to work and coil the clay, then set about building traditional bean pots. When the pots were dry enough to handle, Jeri showed her students how to scrape and sand them until smooth. After applying a mica slip, instead of firing them in a pit, the pots were fired in an open barbeque in Jeri’s backyard using cedar wood. Once cool, the pots needed only to be coated with oil. Then they could be used for cooking. In this hands-on way Jeri passed on her knowledge about micaceous pottery. Her “potteries” (as Jeri refers to them) and miniatures have found homes with collectors from all over the United States and in some foreign countries.

Jeri set a precedent for her daughters early on. Born before New Mexico became a state in 1912, she attended and graduated from high school, unusual for a Taos Pueblo woman of her time.

Bernadette Track

We go by the earth and the stars. That is what dictates our lives and our ceremonies on the Pueblo. There are times when I have to leave my work at the university. Sometimes it’s difficult to straddle both worlds, but it is important.

Bernadette Track learned the traditional ways of pottery along with her first language, Tiwa, in early childhood. After high school, combining her deep love for the arts and strong connection to her Native roots, she attended and graduated from the Institute of American Indian Art. Bernie went on to attend the Connecticut College Summer School of Dance. She was catapulted to Juilliard the following year. There, in a special program with innovator José Limón, she studied modern dance and theater. In 1972, following her training in the dramatic arts at Juilliard, Bernie became a founding member of the Native American Theater Ensemble (NATE). The young Kiowa playwright Hanay Geiogamah helped create this first Native theater company. He was assisted by Ellen Stewart, considered “that great lady of New York theater,” who originated and directed the La Ma Ma Experimental Theater Club. Bernadette was one of sixteen Native actors chosen from the 200 hopefuls who auditioned for Hanay Geiogamah. She toured with NATE and performed off Broadway plays at La Ma Ma.

Longing for her Pueblo Indian traditions and culture, Bernie returned to Taos. She elected to live in the traditional part of the pueblo that has no electricity and only river water. She worked as a Vista Volunteer at Taos Pueblo Day School, modeled for Navajo artist R.C. Gorman, and formed a children's theater. It started when she saw Taos Pueblo children perform Laguna Pueblo tales written by Leslie Marmon Silko in 1986. Bernie and her sister, Soge, felt that the children should be working with Taos Pueblo material, and so the idea for the Taos Pueblo Children's Theater was born. In May 1987 SOMOS (Society of the Muse of the Southwest, the Taos resource center that supports and nurtures the literary arts) got funding for the Taos Pueblo Children's Theater's inaugural performance at the Taos Pueblo Day School. That summer and the following year the Children's Theater played in various locations in Taos, including schools and the Millicent Rogers Museum, and toured to Santa Fe and Albuquerque, playing at schools, the Wheelwright Museum and the New Mexico State Fair. Bernie returned to the stage to perform for DAYSTAR/Rosalie Jones’ Contemporary Dance Drama of Indian America in 1995, and served as a theater consultant for summer workshops conducted in Jemez, New Mexico, by the Art Ranch in 2006 and 2007.

All the while, Bernie was embracing her native roots and incorporating them into her art. Although her training centered on theatre and dance, the pull of the clay was strong. Inspired by her friend, local potter Mary Witkop, Bernie fell in love with the clay which has been her enduring art expression since then. Her micaceous pots follow the tradition of Taos Pueblo, but are infused with Bernie’s own personal style. Some of her large vessels incorporate Taos Pueblo forms and designs, others are simple and unadorned. In some Native theater performances Bernie and other actors wore masks. Besides use as theatrical devices, indigenous cultures throughout the world have used masks for ritual use and storytelling since time immemorial. Both of the influences inspired Bernie to incorporate the mask motif as one of her most powerful creative statements. Ever pursuing new avenues with clay, her pottery imparts a lesson in persistent striving, curiosity and artistic devotion. Bernie has shared her knowledge by teaching micaceous clay classes at the University of New Mexico-Taos and privately. As one of Taos Pueblo’s master potters, her work is in the collection of the Albuquerque Museum and numerous private collections. She is represented by Bryans Gallery in Taos. And still, amidst all of her activities, Bernie continues to promulgate traditional life at Taos Pueblo.

Joann Soge Track

I come from a family of artists, so I can’t help but be inspired to work with the native clay. My muses are my family, my community, and my culture.

As a child Joann Soge Track remembers her grandmother Tonita Suazo working in micaceous clay. From her Soge learned to respect this special clay which would later become important in her life. However, another creative passion occupied her hands and thoughts. She began writing and journaling in high school. In 1968, when she enrolled at the Institute of American Indian Arts, along with courses in theater, modern dance and ceramics, Soge pursued writing. In 1968 the IAIA printed two of her poems and a short story in Writer’s Reader. A year later South Dakota Review published her story “Clearing in the Valley” and the University of Oklahoma Press included “Seven Directions” in its 1970 Anthology of Native American Writers. In 1971 a burning desire to travel took Soge to New York City, then to Paris for the summer. She inhaled French culture. Although fascinated by the art in the Louvre, the Native Art she saw in private collections astonished her. Back in New York City that fall, conversations with Latinos about commonalities in their lives and the struggles of native people led Soge to Cuba. During her two month stay, she helped Fidel Castro with the sugar cane harvest and studied the socialist theories of Marx and Lenin.

Unable to find a job back in Taos, Soge landed next in Tsaile, Arizona, where she studied Indian economics and education, Navajo basketry and creative writing at Navajo Community College from 1972 to 1974. Over the next decade Soge’s writing skills and performing arts background landed her jobs in theater and film. She co-wrote the script for “The Man Who Killed the Deer” (based on a novel by Frank Waters), and was tapped as translator/presenter for the PBS television series “The West of the Imagination.” Soge studied English Literature and Children’s Theatre in college which explains her involvement in a multitude of children’s projects as well. She worked with Buffy Saint Marie and directed “Sesame Street at Taos Pueblo” (filmed by The Children’s Television Workshop in New York) and wrote scripts for “Tiwa Tales” for the Taos Children’s Theater Workshop.

As children Soge and her sister Bernadette had listened to their grandparents and other members of the tribe tell stories. For centuries the stories, told in Tiwa, the language of Taos Pueblo, served as a way to transmit the mores of the culture. Winter or the “time of staying still” was for storytelling. People would gather around the fireplaces to hear men tell hunting tales and women to talk about planting. For the “Tiwa Tales” project, Soge wrote down stories that her grandmother had told her, adapted them to fit contemporary times, then translated them from English into Tiwa for the children to learn. In June 1987 the theater company presented three coyote tales that Soge had written—“The Water Spiller," "Coyote Kills His Wife," and "Coyote and the White-Headed Eagles"—on the Taos Plaza. Using masks to portray the characters, the cast of nine children performed in Tiwa, and the narrator Carpio Bernal translated the stories into English. The bi-lingual performance served two important purposes: it exposed Taos Pueblo children to theater, and the outside world to the Pueblo world view.

An interest in the arts took Soge in another direction. After working at the Wheelwright Museum in Santa Fe and the El Taller Gallery in Taos, she became the assistant curator at the Millicent Rogers Museum. Soge curated Visions 1990, the 11th Annual Art of Taos Pueblo Exhibition and also did community education until 1994. She continued her work as educator as tour guide and tourism coordinator at Taos Pueblo. In 1999 she became a U. S. Census Recruiter and Supervisor. Throughout this time, Soge found a creative outlet in clay. From her grandmother she had learned how to allow her spirit to emerge in the form of pottery. She crafted micaceous bowls, animal sculptures, canteens, tiles and bear fetishes. She demonstrated for Tokyo P. M. magazine, received a commission for two pots from David Rockefeller, and showed her work throughout the Southwest.

Along with her love for the arts, Soge is dedicated to her work as a Lecturer and Rehabilitation Technician for the Department of Vocational Rehabilitation. She spends the rest of her time with her three grandchildren—Jack, Matthew and Reesa—which she counts as her most important work of all.

Dawning Pollen Shorty

I was born an artist, but didn’t know it until I became an adult. Working with indigenous clay from Mother Earth gives me a connection with everything in the universe. I feel it when I work with it. It is what keeps me happy, balanced, and connected. My art is aesthetic and I want to convey the beauty in the human form while at the same time show how beautiful mica clay is.

Sometimes whimsical, always beautiful, Dawning Pollen Shorty's micaceous clay creations arise out of her spiritual connection to Earth. A third-generation artist, she follows in the tradition of her creative family members. Both her parents, potter Bernadette Track and sculptor Robert Shorty, are well known visual and performance artists. They met through the Native American Theater Ensemble in New York. Robert studied under modern dance trailblazer José Limón, and is also a writer. Artists in Pollen’s maternal lineage include her grandmother Jeri Track, her great grandmother Tonita Suazo, her great-aunt Juanita DuBray, her uncle John Suazo and great-uncle Ralph Suazo from Taos Pueblo. On her father’s side, her Navajo grandfather, Dooley Shorty, a master jeweler and WWII Code Talker, taught silversmithing to generations of students at the Intermountain Indian School (now defunct) in Brigham City, Utah.

While attending Taos High School, Pollen opened the Red Rain Gallery at Taos Pueblo. There she showed her first micaceous clay pieces. From 1992 to 1994 Pollen attended museum studies and three-dimensional art classes at the Institute of American Indian Arts. She took courses in archeology, anthropology and photography at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. The first photographer in the family, she wished capture the rapidly changing life at Taos Pueblo. After shooting hundreds of photographs, she put the project aside. It made her uneasy because for decades photographers had exploited the Taos people. Pollen left school to tend bar and work as a cocktail waitress at Albuquerque’s Hyatt Regency. Good earnings enabled her to travel to places in Europe like Paris, Amsterdam and Prague, yet Pollen felt something missing in her life. On the day she realized she was meant to be an artist, she quit her job and returned to clay.

Pollen worked in the traditional way: collecting raw clay from the land and processing it, using natural pigments to paint it, and cedar wood for firing. Already skilled at fashioning pots, she worked on more sculptural pieces like masks. Used to seeing dancers in leotards and in the nude in theater changing rooms, she found beauty in the human form. Inspired by storyteller figures and her father’s sculpture, Pollen created her first nudes out of micaceous clay. The series of work that emerged came about by accident. When the arm broke off a reclining nude, Pollen created and painted a clay Navajo blanket to conceal the repair. A guest of the family liked the piece and commissioned her to make another one. Her new series garnered public attention. When Eight Northern Pueblos association tapped her for a fundraiser, she was written up as an emerging artist. At her first arts and crafts show with the organization in 2009, Pollen’s work sold out. Since then she has exhibited at other venues, including the Millicent Rogers Museum, Eight Northern Pueblo Indian Juried Art Show, and Colorado State University. In 2011 Starr Interiors of Taos hosted Pollen’s first solo show. Today Pollen is represented by Bryans Gallery. in Taos and her work is in private collections.

Pollen considers herself a cultural ambassador. She utilizes her skills to make people aware of traditional and contemporary Native American art. She has lectured and conducted tours at Taos Pueblo and mentored Native American students at the University of Oklahoma’s Headlands Indian Health Career. Her stated goal is to share her knowledge and experience through public speaking, art classes, and art demonstrations. In the last four years Pollen has taught micaceous pottery at the University of New Mexico-Taos, at the Fechin Studio, and in private workshops. She was guest artist at the Worchester Art Museum in Massachusetts, and served in Artist-in-Residency programs at the Taos Municipal Schools and Chrysalis School in Taos. This past summer, Pollen taught a hands-on pottery class for “A Celebration of Pueblo Indian Art and Culture” workshop co-sponsored by SchoolArts of Santa Fe and CRIZMAC, an Art and Cultural Education organization out of Tucson, Arizona. In these many ways, Pollen shares her heritage as an indigenous person, woman and artist of Taos Pueblo.

Asked about her favorite places in Taos, Pollen replies: “At the moment it is at my grandma's old house that I'm fixing up to use as a studio…and its view onto Taos Mountain, the most sacred place on Mother Earth to us Taos Pueblo natives.”

Dakota Star Concha

From a long line of independent women, Dakota Star Concha grew up surrounded by art. In early childhood, however, her world was silent. Born with bilateral-congenital microcia, she couldn’t hear and had no ears. Her mother, Soge Track, raised Dakota and gave her the strength and support needed to overcome her disability. Soge made sure her daughter took the ballet and tap lessons that made her feel graceful. She also introduced her daughter to music; Dakota has fond memories of practicing the violin at the Pueblo. She also appreciates the wide circle of people her mother introduced her to, including friends like modernist painters Louis Ribak and Bea Mandelman and writer John Nichols. In her teens Dakota made her own friends in the literary world when she worked for the World Poetry Bout Association. Founded as the Taos Poetry Circus in 1982 by poets Peter Rabbit and Annie MacNaughton, the organization also hosted some of the nation’s finest slam poets, including Sherman Alexie, Patricia Smith, Quincy Troupe and Wanda Coleman.

The years Soge worked at the Millicent Rogers Museum provided Dakota with lasting inspiration. While her mother worked, Dakota was free to wander the museum’s show rooms, collections, and archives. Exposed to superb examples of Southwest Hispanic and Indian pottery, jewelry, colchas and wooden artifacts, she developed a keen eye and a strong sense of aesthetics. She also learned about the arts in other cultures of the world from the collection of art books housed in the museum’s library.

Art became the mainstay of Dakota’s life, a means to express her emotions, thoughts and dreams. She learned pottery techniques from both her mother and from her father Mieko Concha, who was constantly working in clay or drawing. Dakota also drew inspiration from her grandmother Jeri Track, her great-aunt Juanita DuBray, her aunt Bernadette Track, and her uncles Robert Shorty and John Suazo. With such familial and museum exposure, Dakota became a proficient artist. Besides working in micaceous clay, she also sculpts, does beadwork, sews, and sings. Although she started with pots and masks, she moved away from traditional forms to create her own signature work. She makes clay ladles and has created miniatures to sell at the Millicent Rogers Museum’s annual miniature show. Dakota’s pottery, while functional, is designed to look like something else. For example, her bowls look like flower petals, and the faces of her figurines instead of looking like masks resemble distinct personalities. Lately she has been making necklaces with size 13 beads that look like loose netting similar to fishnet veils seen on women’s hat. Her current ambition is to make a small dress using only beads. These days, howeverm Dakota devotes most of her time to her children—Jack, Matthew and Reesa. She considers them her greatest work of art.

Asked about her favorite places in Taos, Dakota singles out the views she has from Taos Pueblo: the one from her mother’s rooftop on the north side of the pueblo as well as Taos Valley at night seen from the roof of her father’s house on the pueblo’s south side.

Compiled and edited by Elizabeth Cunningham

Photo of Sharon Dry Flower Reyna © 1998 by Nita van der Werff

Photo of Jeralyn Lujan Lucero ©2012 by Barry Norris