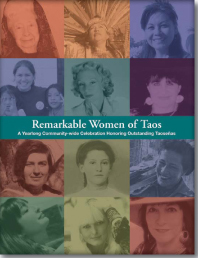

Taos Pueblo Women: A Brief Overview

In this year of Remarkable Women, an often repeated statement “I don’t know any women at Taos Pueblo” prompted the following overview of six representative women drawn from the fields of arts, education and health: Shawn Duran, Diane Reyna, Paula Rivera, Shirley Trujillo, Marie Reyna, and Lillian Romero

Shawn Duran, Motivator, Educator, Activist

Building the Red Willow Education Center on Taos Pueblo, one adobe brick at a time, was a group effort. This place stands in the community as a demonstration of what can be possible when faced with the seemingly impossible.

Building the Red Willow Education Center on Taos Pueblo, one adobe brick at a time, was a group effort. This place stands in the community as a demonstration of what can be possible when faced with the seemingly impossible.

An active community member from Taos Pueblo, Shawn Duran has resided most of her life there, although as a military dependent she was born in Landstuhl, Germany. Inspired by the richness of her native culture and community, Shawn is dedicated to the pursuit of educational, economic and social equality for residents of the Taos Pueblo and oversees the Taos Pueblo Education/Training Division (Taos Pueblo Head Start and Red Willow Education Center). An innovator, she was instrumental in creating and guiding the construction of the Red Willow Education Center. Projects that Shawn developed for the Center include a community computer lab for internet access and job readiness, youth training programs in sustainability, renewable energy and work experience. The Red Willow Center also provides scholarships to Taos Pueblo students in higher education. The Center also supports ‘grassroots’ economic development in agriculture through the emerging Red Willow Community Growers Cooperative and local Co-op store as well as the Red Willow Farmer’s Market in the summers. These venues have created an opportunity for community members to sell value-added products; and received the People’s Choice Award two years in a row from The Taos News.

For education infrastructure development on the Pueblo, she has also worked hand-in-hand with Tribal Government to create the Pueblo’s first Board of Education and Charter. The Pueblo of Taos Board of Education values and recognizes all forms of learning that allows Pueblo of Taos to honor and respect our culture, land, and language by supporting, strengthening, and encouraging our people to recognize the value in our community. To acknowledge the past, act on the present and prepare for the future by asserting and preserving our inherent right to educate our people. By upholding the traditional and cultural values of Taos Pueblo people, we continue to build on the unique talents of each individual (academically, culturally, intellectually, and spiritually), and to help improve the quality of life through educational opportunities.

Shawn is also a member on the Self-Governance negotiation team appointed by Tribal Council. Under her directorship the programs have received national recognition as an outstanding grantee by the Department of Labor in 2007 and, most recently, in 2012 for Innovation, Creativity and Exemplary Program Management from the Office of Indian Energy and Economic Development Division—Department of the Interior in Washington, D.C.

Photo ©2012 by Robbie Steinbach

Diane Reyna, Educator, Artist

The daughter of Annie Cata Reyna (Oke Owingeh) and Tony Reyna (Taos Pueblo), Diane Reyna grew up at Taos Pueblo. Although she didn’t study art formally, she learned about fine Native art through her father’s Tony Reyna Indian Shop. Besides selling quality Indian arts from Taos Pueblo and other tribes, the shop served as a gathering place for artists and craftpersons. This exposure helped develop Diane’s aesthetic sensibility and artist’s eye. Although involved in the arts, she pursued other paths. Diane studied pre-law at New Mexico State University, then completed her degree in University Studies at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. With a focus on journalism, she worked for eleven years in television news as a videographer with KOAT-TV, the ABC affiliate in Albuquerque, and as a video documentary producer. Her video documentary experience cumulated with the production the Peabody award-winning “Surviving Columbus”. This landmark two-hour program documented the history of the Spanish and Anglo-American invasion of the Southwest as seen through the eyes of Pueblo people. The film debuted on Columbus Day, October 12, 1992 on PBS nationwide. The production was coproduced with production teams from KNME-TV in Albuquerque and the Institute of American Indian Arts.

The daughter of Annie Cata Reyna (Oke Owingeh) and Tony Reyna (Taos Pueblo), Diane Reyna grew up at Taos Pueblo. Although she didn’t study art formally, she learned about fine Native art through her father’s Tony Reyna Indian Shop. Besides selling quality Indian arts from Taos Pueblo and other tribes, the shop served as a gathering place for artists and craftpersons. This exposure helped develop Diane’s aesthetic sensibility and artist’s eye. Although involved in the arts, she pursued other paths. Diane studied pre-law at New Mexico State University, then completed her degree in University Studies at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. With a focus on journalism, she worked for eleven years in television news as a videographer with KOAT-TV, the ABC affiliate in Albuquerque, and as a video documentary producer. Her video documentary experience cumulated with the production the Peabody award-winning “Surviving Columbus”. This landmark two-hour program documented the history of the Spanish and Anglo-American invasion of the Southwest as seen through the eyes of Pueblo people. The film debuted on Columbus Day, October 12, 1992 on PBS nationwide. The production was coproduced with production teams from KNME-TV in Albuquerque and the Institute of American Indian Arts.

In 1998 Diane was one of four recipients of the Dubin Fellowship. Awarded annually through the Indian Arts Research Center (IARC) at the School for Advanced Research (SAR), the artist-in-residence provides financial support as well as housing, studio space and materials to mature and emerging Native artists. Diane used her fellowship year to create a series of abstract work on paper using oil pastels and colored pencils. Known for her stone sculpture, Diane also creates works on paper. Her artwork draws from her Pueblo heritage and is inspired by energies in nature.

Currently Diane works as the Student Success Program Coordinator for the Student Success Center at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe. She works closely with students providing academic, creative and cultural support designed to help them persist through college and life. One of the programs she implements at the Student Success Center is the spring and fall orientations. Diane trains student orientation leaders to assist new students with their transition to IAIA. She facilitates a weekly Talking Circle for students to talk about their college experience throughout the semester. At mid-terms and finals week, she prepares blue corn meal (atole) for students, staff and faculty. Diane utilizes her skills in experiential education and facilitation to support her teaching of college success skills courses at IAIA.

Asked about some of her favorite places in Taos, Diane likes walking on the land her father gave her located east of his house. “It has inspiring views especially of Taos Mountain.” She also enjoys walking to the Rio Grande Gorge Overlook on the Rift Trail south of Ranchos de Taos, and taking the drive from Ranchos to El Prado on Highway 240.

Paula Rivera, Museum Curator, Researcher, Indian Market™ Manager

The word ‘art’ is not in our native vocabulary. We don’t have a word for that because everything that we do is a part of that thought. It’s in our daily life, everything that we do, it’s an art form. The pottery that we make, the drums we make, the hides we tan, the horses we take care of, the fields we water, I mean, everything, that’s an art form.

The word ‘art’ is not in our native vocabulary. We don’t have a word for that because everything that we do is a part of that thought. It’s in our daily life, everything that we do, it’s an art form. The pottery that we make, the drums we make, the hides we tan, the horses we take care of, the fields we water, I mean, everything, that’s an art form.

— Paula Rivera quote from film, Painting in Taos

From Taos Pueblo, Paula Rivera now resides in Santa Fe with her two children. Her grandmother, who has always been the center of all the women in her family, raised Paula. The family lived in different places until moving to Santa Fe in her senior year of high school. Paula chose Museum Studies as her educational focus, and earned both an AFA and a BFA from the Institute of American Indian Arts. Her museum career began with an internship at the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, which turned into a position as an Assistant Curator. Paula has also worked at the Millicent Rogers Museum in Taos, and the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture, New Mexico Museum of Art, and the Museum of Contemporary Native Art in Santa Fe. Her professional experience ranges from Collections Care to Conservation and Preservation. Paula’s work as an independent researcher enabled her to curate exhibitions and assist with publications about Native American artists.

Paula’s knowledge of the arts and Native America has strengthened her professional career.

Her nearly twenty years of museum field experience afforded her numerous opportunities to travel, collaborate, research and assist in various projects and exhibitions. Her travels ranged from the West to the East Coasts and down to Cape Town, South Africa. Paula considers the opportunity to meet and work with artists from all cultures and traditions the most important part of her career.

Currently, Paula is working with the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts (SWAIA), Santa Fe Indian Market, as the Indian MarketTM Manager. This position keeps her in the background, taking care of the logistics of the Market. Her responsibilities entail managing the timeline for this event, while working with artists, food vendors and other entities that help to make this event occur. Amidst all these experiences and travel, Paula maintains strong ties with her family and her community of Taos Pueblo. More information on SWAIA.

Shirley Trujillo, Agriculturalist, Tutor

We need to be aware of what is happening around us, and not let corporations control our seeds and food sources. It is important to revive ancient customs of growing our food, relying on the medicinal values of our native plants.

We need to be aware of what is happening around us, and not let corporations control our seeds and food sources. It is important to revive ancient customs of growing our food, relying on the medicinal values of our native plants.

Shirley Trujillo was born in Albuquerque and is a community member of Taos Pueblo. While raising four children in Taos, she earned a Bachelor's degree from the University of New Mexico. Shirley also attended Southwestern Indian Polytechnic Institute and Northern New Mexico Community College. A passionate gardener, Shirley was instrumental in developing a very successful sustainability greenhouse project at the Red Willow Center at Taos Pueblo. To expand her knowledge base, she visits different farms both in New Mexico and outside the state. “It’s great to learn new and old ways of growing, and to meet new people.” And Shirley has learned from them because every farmer and gardener has specific ways of producing food. She loves teaching and learning. In recognition of her commitment and talent, activist Winona LeDuke invited Shirley to attend the worldwide Slow Foods Conference in Torino, Italy in 2007.

As manager of Red Willow Growers, she has worked with Taos Pueblo Youth Interns to grow their own produce and help start Red Willow Farmers Market. Her high school interns were the hands and hearts that started seedlings and harvested each season. To broaden their horizons, Shirley takes her interns to surrounding farms. At Red Willow she has gained knowledge about operating solar panels and solar wells as well as working with a biomass furnace that heats the buildings and greenhouse. Throughout her work Shirley strives for balance. As she puts it: “New technology is great to learn but I love the old and simple ways of growing and saving seed for the next growing season like my grandparents did. Growing is my connection with my culture and my community.”

In her free time, Shirley walks in the mountains and the forests to interact on an everyday basis with plants and nature. Additionally, she enjoys “every aspect of music; new and the old, mostly reggae!” and visiting “ancient places like Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon.”

Photo ©2012 by Robbie Steinbach

Mildred Young, Beadworker, Educator

I tell the children I teach, to go home today and ask your parents, grandparents, relatives, elders, and community members what they did when they were children and ask them to teach you some of our native language – Northern Tiwa. They have great resources around them, so make use of it. When I hear Pueblo children speak my language (Northern Tiwa), it sounds like music to my ears.

I tell the children I teach, to go home today and ask your parents, grandparents, relatives, elders, and community members what they did when they were children and ask them to teach you some of our native language – Northern Tiwa. They have great resources around them, so make use of it. When I hear Pueblo children speak my language (Northern Tiwa), it sounds like music to my ears.

Mildred Young was born in Taos in 1958. She attended Fort Lewis College in Durango, Colorado. Using techniques learned from her grandmother, family, relatives, and community, Mildred creates traditional beaded moccasins, and hopefully “plants a seed” in children to continue to learn their native language. After raising five children, she earned a Certificate in Human Services and a Bachelors Degree from the University of New Mexico. In addition to teaching Tiwa and tutoring, she is an education technician at Taos Day School and an avid participant in her community at Taos Pueblo.

Photo ©2012 by Robbie Steinbach

Note: Thanks to photographer Robbie Steinbach and writer Lyn Bleiler who graciously granted permission to use photos and text from their book A Precarious Balance: Creative Women in Taos (2012). The book features 50 women of Taos and is available through blurb.com.

Marie Reyna, Artist, Director of Oo-Oonah Art Center

Marie Reyna was honored as an Unsung Hero by The Taos News three years ago. The article, written by Virginia L. Clark, was posted online on Friday, October 23, 2009. It is used with permission of The Taos News. © 2012 The Taos News. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

“Tradiciones - Marie Reyna: Keeping Tradition Alive through Arts”

Marie A. Reyna almost died in 2008 from scleroderma, a rare autoimmune disease. But still she worked, along with her staff and volunteers, at her Taos Pueblo Heritage Project, providing for Taos Pueblo children, a “heritage” more than a 1,000 years old.

Marie A. Reyna almost died in 2008 from scleroderma, a rare autoimmune disease. But still she worked, along with her staff and volunteers, at her Taos Pueblo Heritage Project, providing for Taos Pueblo children, a “heritage” more than a 1,000 years old.

She says that creating the Heritage Project and serving two decades as Oo-Oonah Art and Education Center executive director are the ostensible reasons for her selection as a 2009 Unsung Hero. But she says her work is about much more than just one person.

“This is supposed to be about me,” she muses during a September interview for this article. “But it’s not about me. It’s about my staff and students. Without that, I don’t have a program.”

Recognizing all the people around her is typical of Unsung Heroes, those people the community sees working tirelessly behind the scenes, saying about their own efforts, “So what? Big deal …”

Marie Reyna has just finished kidney dialysis for the week. The summer phase of the Heritage program is winding down. She is grateful for the gains in her health.

“It was just this spring that I started feeling like a normal person again,” she says. Peace settles across her face. “Last year was just a matter of trying to survive. This spring I was able to provide my students with the full program. Once I got on dialysis, my body was able to recharge through that technology and now I’m able to address things not done last year, like applying for money for stuff.”

“She’s very productive, a very productive person,” says her father, Tony Reyna, former governor of Taos Pueblo, owner of Tony Reyna’s Indian Shop and one of the few remaining survivors of the Bataan Death March.

“And a lot of people don’t know it — especially the parents,” Tony Reyna adds, quietly emphatic about his daughter’s unceasing efforts on behalf of Taos Pueblo children —Taos Pueblo’s future. In the face of an expanding digital culture across the globe, traditional societies are hard pressed to inculcate the importance of culture.

In 1985, Reyna and Joseph Concha started Oo-Oonah Art Center (Oo-Oonah means child in Tiwa) on the site donated by Rose Cordova for Constantine “Stan” Aiello’s dream of an Indian children’s art center, back in the ’70s. Aiello died during the opening, and Taos Indian arts education almost died with him.

While an accomplished silversmith herself (“I took every jewelry class New Mexico State University offered,” says), it is the legacy she passes on to Taos Pueblo children that garners her election as an Unsung Hero.

“The future of our community lies in the building of self-esteem, traditional Indian life-skills and a positive learning atmosphere for our children,” Reyna says about Heritage Project. “The project insures that our children have a strong sense of identity and are culturally tied to their community.”

The Oo-Oonah students have been juried into local, national and international exhibits and received numerous awards and ribbons over the years. Student work has been exhibited at Santa Fe’s Museum of Indian Art and Culture and at the Governor’s Gallery in the State Capitol. Works have also been seen internationally in the Japanese cities of Tokyo, Kyoto and Yokohama, as well as in Poland during the Krakow 2000 festival.

Working closely with Taos Day School and Taos Municipal Schools, the center attracts student dropouts, who can enroll in the Oo-Oonah’s Vocational Education Program of silversmithing if they are 18 or older. Using pottery as an example, Reyna points out that a pot is a “utilitarian” item.

Yet it just so happens, she says, “that the non-Indian was attracted to its beauty and wanted it to be put in their house.” Despite the many stylized versions of Indian pottery, and despite the fact that it is highly sought after, “the main reason for it in our pueblo world is for its utilitarian use. But when it comes to traditional ceremony, you’re going to have to have these things,” Reyna says.

“The reason we want them to learn these ways is because they will need to produce these things. We have to use the knowledge from the past thousand years from now on,” so the old ways continue unbroken. The Heritage Program teaches children to behave well; to participate in their culture; to vitalize the Tiwa language; to respect the site of Taos Pueblo, its buildings and lands, the vegetation, the animals and, of course, the community.

“To have respect for themselves and each other,” she adds. “Because they are each others’ brothers and sisters and we are their aunts and uncles.”

The program has pending grant approvals from the Chamisa Foundation and the Phillips Family Foundation, established to provide support to tribal organizations from the Río Grande Pueblos. Through the years, Reyna’s fundraising has repeatedly garnered support from the N.M. Arts Division of the National Endowment for the Arts and the Healy Foundation.

“To be Indian means we have a moral obligation to our ancestors — they didn’t know who we were, but they were willing to lay down their lives for us and we’re doing the same thing for the kids coming up,” Reyna reminds us. “They have a moral responsibility to their Taos Pueblo, to keep it right, to keep it strong.”

Pictured, Marie Reyna and Ruben Romero, one of her successful art students.

Photo ©2012 by Nancy Castelli

Lillian Romero, Community Worker and Champion of the Elderly

Honored this year as an Unsung Hero, the following profile by Rooney Pitchford appeared in a 2012 Special Section of The Taos News. The article is printed in full as a testimony to how hard Taos Pueblo women work for the good of their community. It is used with permission of The Taos News. © 2012 The Taos News. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

“Lillian Romero: Getting the Job Done”

“Lillian Romero: Getting the Job Done”

For her years of work as a community worker and representative for the elderly of Taos Pueblo, The Taos News honors Lillian Romero as an Unsung Hero.

After a decade of lobbying for funds from the state of New Mexico, Romero and her support team acquired the funds necessary to build a senior center on the Pueblo, which now serves more than 50 elders per day, offering services from home-delivered meals to free transportation to and from the grocery store.

Born and raised on Taos Pueblo by parents Julian and Anita Romero, Lillian says her upbringing contributed to what would become her lifelong dedication.

“About a fourth of my time was spent with my grandparents, and they were very traditional people,” said Romero during an interview at the senior center, while she took a break from work in the kitchen.

“One of the things that inspired me to get into this field was when my grandmother started living with my mother. At that time I wanted somebody (to help), because my mom was so stressed by care of her.”

In the years following her upbringing, Romero witnessed a growing trend for the elderly of the Pueblo; often, with family members needing to work in order to support the family, the elders were left alone. “I’ve seen grandmas who have nobody to take care of them during the day because their families are working and can’t afford to leave their jobs.” When Romero was in her 30s, she began to seriously consider the possibility of creating an organization on the Pueblo that could provide company as well as services to those left at home.

Research revealed that there are only two nursing homes on Native land in the United States. Federal funding, Romero found, simply wasn’t enough to support the system she had in mind. But Romero found she was not alone in her dream. As she expressed interest in the project, she says, pressure came from friends and the tribal council to explore other avenues to success.

“I realized we were part of the state, and we needed to get something from the state,” Romero says. But advocating for the Pueblo in front of legislative panels in Santa Fe would reveal itself to be a grueling process, and one that took years to produce substantial results.

Romero and a team of grandmothers from the Pueblo began making trips to the State House of Representatives and Senate during winter legislative sessions, beginning a process of trial and error that, though beginning with a slow start, ultimately brought rewards.

“We would talk to anyone who would listen,” Romero said, adding that she and her grandmother friends would often get up early in the morning to begin the trek to the Roundhouse. “We would sit there until they’d talk to us, finally.”

While Romero said that as a state institution, they weren’t technically allowed to lobby, they found that, for the first time, the Legislature was dealing with Native Pueblos. “We’re lucky to have the state.”

Each spring, Romero wrote for as many proposals and grants as she could find, a practice she continues today. At first, the work yielded small-time results, usually a couple of thousand dollars at a time, but after 10 years of asking, Romero landed $1.2 million to make her dream a reality.

With no time to waste, Romero and her team sat down with Steve Robinson, an architect from Santa Fe, to get the project under way. “We sat down and told them exactly what we wanted.” Ground was broken in 2009 and the senior center was completed in 2010. The center includes a demonstration kitchen, an exercise room, and a nap room.

Romero describes the center as a “focal point where people come for anything they can think of.” The most prominent services offered are meals and information regarding medical insurance. More than 50 meals are delivered to elders at home every day, and the center provides up-to-date information on Medicare and Medicaid.

But the job isn’t nearly complete, says Romero, and it’s one that takes constant work both with the state and on the Pueblo. “I’m planning to expand ... I’m putting out feelers.”

The center only has one bed at the moment, and Romero would like to see an expansion into a full adult-daycare center and nursing home. To that end, Romero continues her work with the state, writing proposals every May and seeking grants and donations from the state and charity organizations, respectively. “We’re not doing as much as we want to,” she says.

The center runs five days a week (funds don’t allow seven-day service), and serves as a meeting spot for Pueblo organizations. “We’re getting more people to come to the center,” Romero says, adding that representatives of outside groups are often shown the senior center. “It’s a show place. This is a nice building. We have a lot of meetings here.”

With regard to being an Unsung Hero, Romero dodges the praise, instead passing it onto both the workers at the center and the elders who pressured her and supported her as she fought for state funds, many of whom are no longer alive. “My staff are unsung heroes,” she says. “They’re the ones who are providing.”

Romero hopes to retire soon, but predicts she won’t be absent from the center she helped to build. “This is my home. I was born here and I plan to stay here,” she said. “I’m gonna leave a plan ... I’ll probably be involved somewhere, because I don’t want to leave. It’s been my longtime dream.”

Pictured, Lillian Romero (in foreground) with her staff. Photo © 2012 by Tina Larkin, The Taos News

compiled and edited by Elizabeth Cunningham