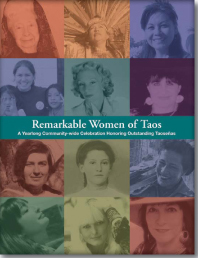

Dollie Valdez Mondragon

“I will gladly share my family history as well as my knowledge of the history of La Loma Plaza, an area in Taos where I was born and raised and still reside today.” A woman with a generous heart, Dollie Valdez Mondragon was born and grew up in what is now the La Loma Historic District. La Loma (the hill) has the distinction of being one of two fortified plazas in New Mexico that remains residential. In the early 1800s Spanish pobladores (settlers) petitioned for land to build a new settlement just outside the boundaries of the old town of Taos. They built La Plazuela de San Antonio (The Little Plaza of Saint Anthony) on a hill as a fortress against Indian attacks. Low, flat-roofed adobe houses with shared walls faced onto the open plaza (square) in the center. The rear walls faced outwards with no windows, forming an unbreachable battlement much like the centuries-old walled Spanish town of Avila. Residents could walk on the rooftops. Guards posted there had the added advantage of the hill’s height to keep watch from.

“I will gladly share my family history as well as my knowledge of the history of La Loma Plaza, an area in Taos where I was born and raised and still reside today.” A woman with a generous heart, Dollie Valdez Mondragon was born and grew up in what is now the La Loma Historic District. La Loma (the hill) has the distinction of being one of two fortified plazas in New Mexico that remains residential. In the early 1800s Spanish pobladores (settlers) petitioned for land to build a new settlement just outside the boundaries of the old town of Taos. They built La Plazuela de San Antonio (The Little Plaza of Saint Anthony) on a hill as a fortress against Indian attacks. Low, flat-roofed adobe houses with shared walls faced onto the open plaza (square) in the center. The rear walls faced outwards with no windows, forming an unbreachable battlement much like the centuries-old walled Spanish town of Avila. Residents could walk on the rooftops. Guards posted there had the added advantage of the hill’s height to keep watch from.

Dollie remembers playing on these roofs as a child. She grew up hearing stories about her grandfather Inocencio Valdez who claimed and owned the northwest section of the plaza. He also donated some land for a family chapel. Built in the 1860s, it was named after the village’s patron saint, San Antonio de Padua. The families of La Loma used the chapel for devotions, rosary recitation, velorios (wakes), and occasionally for mass. Dollie learned that Ino (as the family called him), an educated man for his time, taught school at Taos Pueblo in the 1880s. He later served as maestro (teacher) in the village of Arroyo Hondo, eleven miles north of Taos. A member of the Taos Militia, he also edited a Taos newspaper, El Heraldo de Taos. Dollie never met her grandfather. He died in 1906, nearly three decades before her birth. Three days after Inocencio’s death, his wife Octaviana gave birth to his namesake. Baby Ino died within hours. The chapel bell tolled to announce the Valdez family’s double tragedy.

The bell peeled again on a happier occasion: the marriage of Dollie’s father Manuel Valdez to Azucena “Susie” Gonzales. The couple established a residence of their own in La Loma. Two sons, Carlos and Fernando, preceded the arrival of a girl christened Leanor. However, when her brothers referred to her as “La Dollie”, the baby doll that cried, she became known by that name. Like her grandfather and her parents, Dollie and her siblings attended St. Joseph’s Catholic School. The nearby Our Lady of Guadalupe parish ran the school; the Sisters of Loretto taught classes for grades 1 through 8. Of all her subjects, Dollie most enjoyed dancing, singing, and acting in the school plays. At home she followed her mother’s lead: “Mama was always humming, singing or whistling as she set about her work.” Dollie’s father liked hearing his daughter sing. Whenever family or friends dropped in, he would ask her to sing for them: “She has a soft and melodious sweet voice.” So encouraged, she learned several songs by heart, both in English and in Spanish. Later at Taos High School, Dollie became involved in photography (she took pictures for the yearbook) and joined the Glee Club. With some guitarist friends providing accompaniment, Dollie sang canciones rancheras (traditional rural folk music, often called cowboy songs, originating from ranches in Mexico). The group entertained as a team and made recordings. At age 16 Dollie took the stage name of La Muñequita (The Little Doll). The group performed at Mike’s Night Club and the St. Francis Auditorium in the Taos area and traveled to San Luis, Trinidad and Walsenburg in southern Colorado.

In 1953 Dollie married Teodoro “Ted” Mondragon. The newlyweds moved to Pueblo, Colorado, where Ted worked as a mechanic at the ordinance depot there. Five years later they returned to Taos; their six children—Catherine, Dominic, Teresa, John, Veronica, and Nicole—became the next generation to grow up in La Loma. Dollie and Ted could be considered the guardians of La Loma Plaza. In the 1960s, when the children were small, their parents spearheaded efforts to create a park in the central plaza. The Mondragons and their youngsters worked side by side with neighbors to gather rocks to pave a seating area for and to build walls around the park. Taos artists Louise Gautier and Mary Shivas pitched in to help, along with the Riveras, Trujillos, and other descendents of La Loma’s original settlers.

Around this same time, Dollie and Ted supervised renovations to the San Antonio Chapel. Dating from the 1830s, the chapel originally had a flat roof. When reconstruction became necessary, it was replaced with a pitched roof and wood cupola. Dollie and Ted did much of the painting and routine maintenance themselves. The couple served as mayordomos (church stewards) at both the Parish at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church and the San Antonio Chapel. Whenever the chapel needed remudding or repairs, they called on the parishioners for assistance.

Ted, who worked primarily as a mechanic at the molybdenum mine in Questa, never intended Dollie to work. However, when her Uncle Felix Valdez, editor of the Spanish Section of the local paper El Crespusculo (The Dawn), heard that she wanted to work, he convinced her to help Jack Boyer, director of the Kit Carson Foundation (now the Taos Historic Museums). At the time, Jack dreamed of preserving buildings representative of the diverse cultural history of Taos. He had established the Kit Carson Home (representing the mountain man era) as a museum. Jack hired Dollie as a receptionist there. Within weeks she began helping Helen Blumenschein set up rooms for the Blumenschein Home. (Jack Boyer envisioned this museum as representing the Taos art colony.) Dollie helped clean up the house, lay out rooms--the kitchen, dining room, bedrooms and bath, and the studio complete with Ernest Blumenschein’s easel—and place furniture and other objects. When finished, the museum represented the artistic lives and careers of the three Blumenscheins: Ernest, his wife Mary, and their daughter Helen. From 1962 when the Blumenschein Home opened as a museum, Dollie worked there as receptionist and interpreter. She also did odd jobs like watering and maintaining the garden around the plaza well. She liked talking to people who visited and enjoyed sharing the history of the Blumenschein Home and Taos with visitors. Additionally Dolly and her youngest daughter Nicole helped Rowena Martinez who was in charge of the historic annual fashion show at the Hacienda de los Martinez, the restored ancestral home of Padre Antonio Jose Martinez. (Jack Boyer envisioned the Martinez Hacienda as the interpretive agent for the 400-year-old Hispanic presence in Taos.) Dolly wore her grandmother Octavia's clothes on these occasions. For over 40 years Dollie worked as the museums’ cultural ambassador. Additionally, whenever anyone requested a tour of La Loma Plaza, she happily imparted her knowledge.

Although Dollie never pursued university studies—“My college was having my children. I left the rest up to the Lord,” she says with a smile—she took a keen interest in history. While working at the museums, Dollie started writing down what she remembered about growing up in La Loma and its history. For years she compiled and filed away her handwritten notes. One day she pulled these together into a hand-bound book she designed and titled Sombras en La Loma (Shadows of La Loma). In this volume, Dollie brought three generations of the Valdez family to life through history and anecdotes. The dedication to her family reads: “Cast tall shadows of small images and make rainbow reflections.” Written for her children to preserve the history of La Loma and three generations of the Valdez family, Dollie’s book documents a way of life that no longer exists. Her vivid account of Hispanic traditions, customs and folklore of 19th and 20th centuries makes this labor of love an invaluable addition to Taos history. Most importantly, it conveys the graciousness and charm of Dollie herself.

By Elizabeth Cunningham

Photo of Dollie Mondragon modeling historic clothing worn by her Grandmother Octavia Valdez at the Hacienda de los Martinez, 1995. [Photo by Larry Torres]